Peer-Reviewed Article · Nov 26, 2019

Is global warming affecting the weather? The role of emotion, politics, and experience in public opinion

By Matthew Cutler, Jennifer Marlon, Peter Howe and Anthony Leiserowitz

We are pleased to announce the publication of a new research article, “‘Is global warming affecting the weather?’ Evidence for increased attribution beliefs among coastal versus inland US residents” in the journal Environmental Sociology.

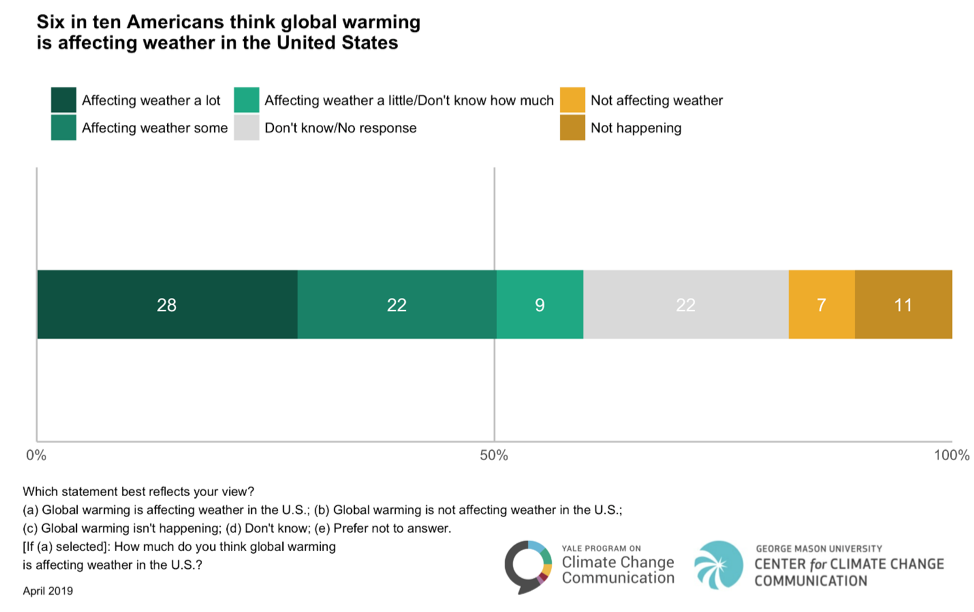

Public opinion about climate change often reflects differences in political ideology, with liberals expressing greater understanding of and concern about the issue than conservatives. But other factors can also play a significant role in shaping climate opinions. In this study we investigated which factors lead people to think that global warming is affecting the weather. As context, our most recent national survey (April, 2019) found that 59 percent of Americans think global warming is affecting weather in the United States.

This paper uses our national survey data from 2013 to 2017. We find that the strongest predictor of the perception that global warming is affecting the weather is worry about global warming, even after controlling for political ideology. The more people worry about global warming, the more likely they are to say that it is affecting the weather. The study doesn’t distinguish whether belief that global warming is affecting the weather increases levels of worry or vice versa – but our prior research suggests that both are true.

After worry, political ideology is the second strongest predictor in our analysis. Consistent with prior research, liberals are more likely to say global warming is affecting the weather than conservatives.

We found no correlation between direct experience of extreme weather events and public perception that global warming is affecting the weather. Many studies have looked for evidence of such a link, with mixed results. Some studies find no link and others find a small, but significant link (see here for a review of this literature by members of our research team).

Understanding how experience shapes climate opinions continues to be an active area of research. Results often vary due to differences in measures of direct experience, public opinion, or different populations being studied. A reasonable conclusion is that the effect of extreme weather experience on public climate change opinion has thus far been small compared to other factors like worry and political ideology. This, however, could change in the future as extreme weather events become more frequent and severe, and critically, as public discourse connecting the dots between climate change and extreme weather increases.

Finally, this study uniquely investigated the role of place in shaping public perceptions that global warming is affecting the weather. Controlling for worry, political ideology, and other demographic variables, we find that people living in coastal counties are more likely to say global warming is affecting the weather than people living in inland counties. This is an intriguing finding that place matters – that people are embedded in local socio-cultural contexts and social networks that also influence their perceptions. For example, this may help explain why Republicans in coastal California and New York are more likely to believe global warming is real, human-caused, and a serious threat than Republicans in interior states like Oklahoma and Nebraska. Much more research is needed to investigate the influence of such local, social, and cultural factors.

The full article is available here to those with a subscription to Environmental Sociology. If you would like to request a copy, please send an email to climatechange@yale.edu, with the subject line: Request Global Warming Affecting the Weather Paper.