Peer-Reviewed Article · Aug 8, 2017

Public Opinion: Is there an economy-environment tradeoff?

By Matto Mildenberger and Anthony Leiserowitz

Filed under: Policy & Politics

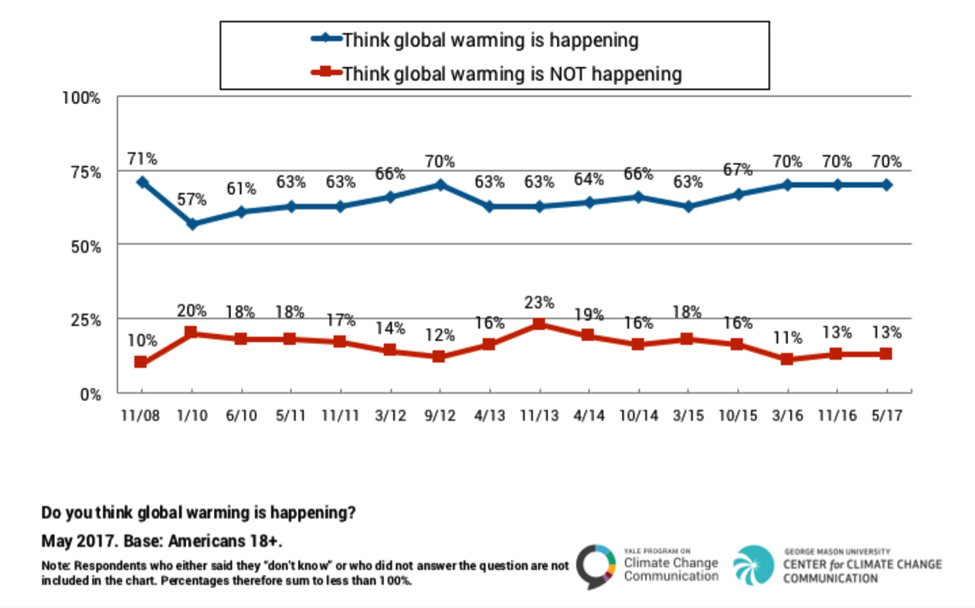

Between 2008 and 2012, multiple surveys found that US public beliefs and attitudes about global warming declined by over 10 percentage points. For example, our surveys found that public belief that global warming is happening fell from 71% in 2008 to a low of 57% in 2010 before beginning to rebound.

What happened? Analysts have suggested many possible causes – from cold weather events to political polarization. And almost everyone has assumed that the Great Recession played a central role. Our recent article in Environmental Politics challenges this view.

Politicians and academics often assume that public preferences for economic and environmental policies are substitutes. When the economy is bad, the public cares more about short-term economic needs and less about long-term environmental risks. When the economy improves, it provides space for the public to worry more about environmental harm.

Surprisingly, there isn’t a lot of evidence demonstrating this relationship in practice. While several studies find some correlation between economic insecurity and climate opinions, there is no robust evidence that this association is causal.

To examine this relationship in the context of climate change, in 2011 we recontacted the same individuals who completed our 2008 survey. This allowed us to assess how individual-level climate beliefs and attitudes in the U.S. changed over time. This within-subject data also allowed us to evaluate whether the Great Recession caused the declines in public climate change beliefs and attitudes.

The analysis led to a consistent and surprising result: The Great Recession did not change U.S. climate change beliefs or attitudes at all. Instead, the change in U.S. climate change opinions observed between 2008 and 2011 is better explained by other factors, such as cues from political elites.

We found no association between declines in local economic conditions and climate beliefs. Changes in self-reported household income and the degree to which our survey respondents felt they had been impacted by the Great Recession did not predict changes in individuals’ climate change opinions between 2008 and 2011. Neither did state, county or zip-code level unemployment rates. Neither did changes in local housing market conditions or local gas prices.

We also found no relationship between declines in local economic conditions and support for various climate policies. Many respondents became less supportive of climate policies between 2008 and 2011– but the individuals who were most hard-hit by the Great Recession were no more likely than others to reduce their support for climate policies.

So what happened? If it wasn’t the Great Recession, why did public climate change beliefs and attitudes decline so dramatically? The likely culprit is a parallel shift in American politics that happened during this time, including the rise of the Tea Party. We found a significant association, for example, between changes in the environmental voting record of a survey respondent’s congressional representative and the shift in a respondent’s climate beliefs and attitudes between 2008 and 2011. Political scientists have long argued that public opinion responds to messages and cues from political elites. Our results are consistent with this theory.

This finding is both good and bad news for climate advocates. On one hand, it suggests that public support for climate policy is unlikely to be affected by even large economic swings. Americans are likely to continue to support climate action in good and bad economic times.

However, it also indicates that public opinion on climate change is very sensitive to changes in the Republican and Democratic party platforms and politicians’ talking points. This suggests that engaging Republican leaders in the issue will be important not just to the passage of climate legislation, but to shifting public opinion as well. It may also suggest that efforts to reframe climate change as a health, moral, religious, economic, national security or other kind of issue may help at least some Americans engage the issue in a more constructive way.

The article is available here to those with a subscription to Environmental Politics. If you would like to request a copy, please send an email to climatechange@yale.edu, with the Subject Line: Request Environmental Politics Paper.