Climate Note · Jul 20, 2023

Messages about harms of fossil fuels increase support for renewables, with or without a moral emphasis

By Abel Gustafson, Matthew Goldberg, Sanguk Lee, Miriam Remshard, Andrew Luttrell, Seth Rosenthal and Anthony Leiserowitz

Filed under: Messaging

Update February 2025: This publication has been updated with information from the peer-reviewed article, published in the journal Science Communication. The updated version is available here.

We are pleased to share the findings of a new study, conducted in collaboration with the Center for Public Engagement with Science at the University of Cincinnati. This study examines the persuasive effects of moral appeals on public support for the transition from fossil fuels to clean, renewable energy.

The global transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources (such as solar and wind) will be greatly affected by social factors such as public opinion, consumer demand, and political support. Political polarization over renewable energy has increased in the U.S. over the past five years. This divisive political climate underscores the importance of finding ways to communicate about renewable energy across different segments of the public.

One approach is appealing to people’s moral foundations. Some research has argued that morality is a primary source of people’s opinions on a wide variety of issues. Prior studies have found that moral appeals can be persuasive for diverse people – particularly when they highlight moral principles held by the audience. For example, a message might be more persuasive if it argues that we should transition to renewable energy because fossil fuels are unethical due to pollution harming innocent people (violating a common moral principle) and to fewer people if it argues that we should make this transition because of climate change. Similarly, a message could argue that fossil fuels are unethical because the pollution contaminates the cleanliness of the natural environment – activating another key “moral foundation” of purity.

Here, we report findings from a recent experiment testing whether persuasive effects are enhanced by explicitly emphasizing the moral and ethical aspects of different energy sources. Although all information about the harms of fossil fuels and benefits of renewable energy could be interpreted as having some degree of moral implications, it is important for communicators to know if it is beneficial to explicitly make a strong moral claim as a reason to transition away from fossil fuels. Therefore, our study tested the effect of explicitly calling out those ethical implications, compared to only describing the negative impacts of fossil fuel use without an explicit statement about morals and ethics.

Overall, we found that explicitly emphasizing the moral aspects of the issue did not provide a boost in either persuasiveness or message durability. Put simply, we found that the messages describing the negative effects of fossil fuels and advantages of clean energy already had strong and durable effects and nothing was gained by adding an explicit claim about ethics. While this is only one study, the findings suggest that direct statements about the morality or immorality of different energy sources do not necessarily enhance the persuasiveness of messages.

In our study, research participants were randomly assigned to watch one of five animated videos. Two non-moralized videos explained how fossil fuels can harm human health and the environment, respectively. Two “moralized” videos contained the same information but also included additional arguments about why this means using fossil fuels is inherently immoral, because doing so harms innocent people or contaminates the purity of nature, respectively. The image below provides an example. The fifth video, which provided information about an unrelated topic, provided the control (baseline) condition.

We found that all four messages were effective at changing beliefs about renewable energy and support for an energy transition. However, adding the specific moral claims (“this is unethical”) did not increase the persuasiveness of the message. Instead, all messages were similarly effective.

Persuasive Effects Over Time

In addition to investigating the immediate persuasive effects of the video messages, we also tested how long the persuasive effects lasted. Most studies on persuasion only measure immediate effects – that is, how attitudes and opinions are affected right after persuasive messages are presented. But it is critical to also understand how durable these changes are. Persuasion that quickly fades away might not be practically useful, especially when the desired outcomes are longer-term, such as changing daily habits or voting in a future election.

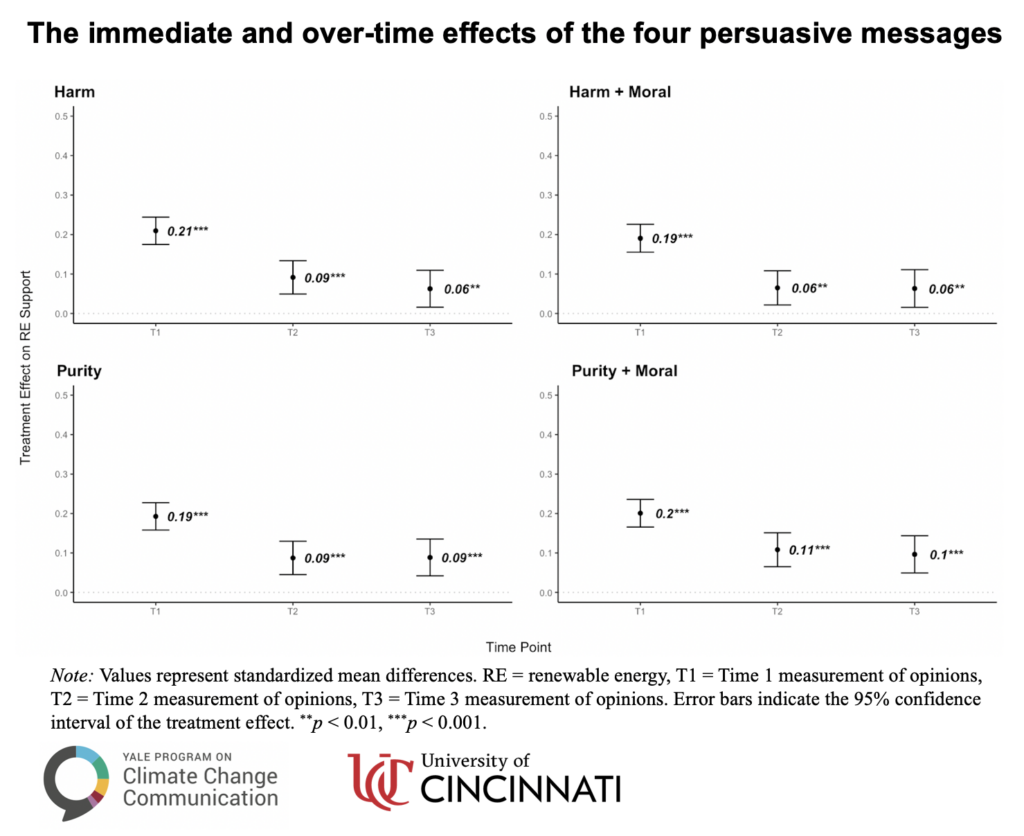

Accordingly, we measured participants’ opinions at three different times: immediately after seeing the message, about 10 days later, and then finally after another 10 days. This allows us to measure how much the initial changes in opinions persisted (or decayed) over time. Our findings (visualized in the figure below) showed that all four messages – whether moralized or not – had durable persuasive effects on people’s support for a transition to renewable energy. Across the four different messages, between 32% and 48% of the original treatment effect was still present after three weeks. However, we found no evidence of an added boost in durability from the explicit moralization of the message. Instead, there was similarly strong durability across all versions of the message.

We are currently preparing the full paper for submission to a scholarly journal.