Peer-Reviewed Article · Nov 29, 2022

Does personal climate change mitigation behavior influence collective behavior? Experimental evidence of no spillover in the United States

By Karine Lacroix, Jennifer Carman, Matthew Goldberg, Abel Gustafson, Seth Rosenthal and Anthony Leiserowitz

Filed under: Behaviors & Actions, Beliefs & Attitudes and Messaging

We are pleased to announce the publication of a new article, “Does personal climate change mitigation behavior influence collective behavior? Experimental evidence of no spillover in the United States.”

Both personal and collective action are needed to reduce carbon emissions and limit the impacts of climate change. Even so, solutions to climate change are often presented as a trade-off between personal and collective behavior. Some argue that people taking individual actions to reduce climate change may be less willing to participate in collective actions because they feel like they’re already doing enough, and vice versa.

Does reminding people of the personal mitigation actions they have taken (e.g., reducing food waste, using low energy light bulbs) reduce their willingness to take collective action (e.g., engaging/participating in political behavior and supporting policy change)? Alternatively, does reminding people of their past personal mitigation behavior lead to an increase in (i.e., positively “spill over” to) willingness to take collective action?

To answer these questions, we conducted two experiments. Participants in each experiment were randomly assigned to one of four conditions. In one condition, participants were provided a checklist of personal climate-related actions (such as turning off electronic devices when not in use), and indicated which of those actions they currently take (Checklist-only condition). In another condition, participants read a message emphasizing the importance of both personal and collective climate mitigation behaviors (Message-only condition). In a third condition, participants completed the checklist and read the message (Checklist + Message condition). And finally, we included a control condition in which participants read a message unrelated to climate change (Control condition). After completing one of these four conditions, participants answered questions about their environmental identity, willingness to perform collective behaviors, support for a carbon tax on individuals, and support for a carbon tax on companies.

The design was similar across the two experiments, except that different messages were used in the Message-only and Checklist + Message conditions in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2. In Experiment 1, the message emphasized that both individual and collective behavior contribute to the goal of reducing climate change. In Experiment 2, the message emphasized the benefits of collective behavior for both human health and the environment (i.e., plant and animal species). We then examined whether there were spillover effects of the checklist and/or messages on behavioral willingness and policy support.

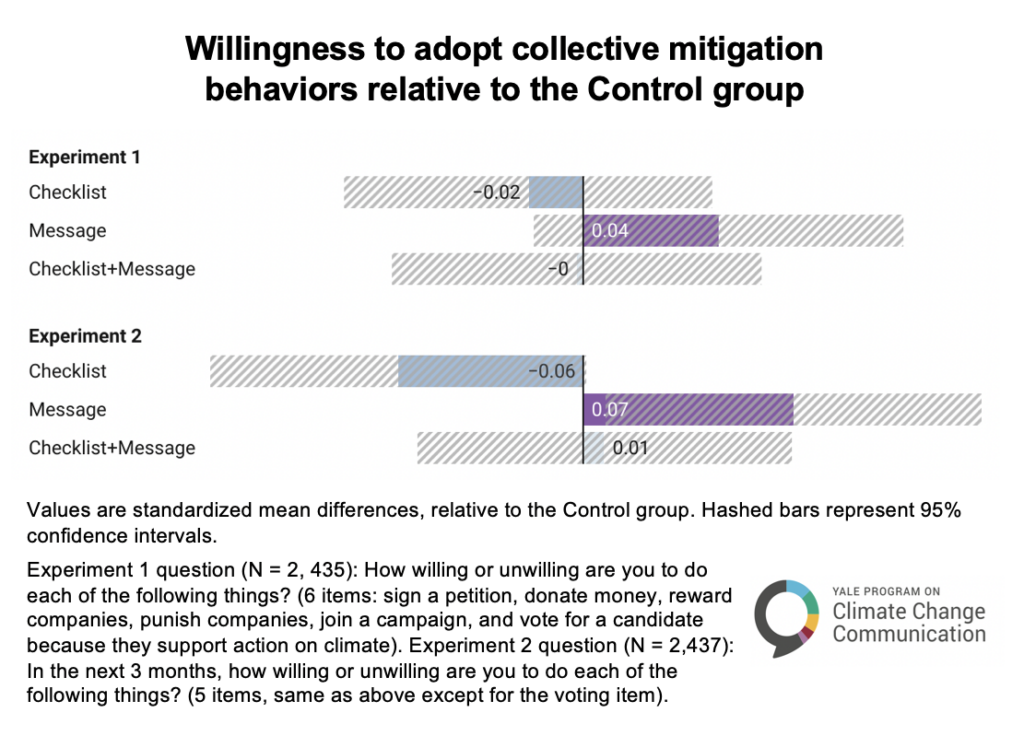

Results: first, looking at behavioral willingness, we found that reminding people of the behaviors they have personally done in the past (Checklist condition) had no influence on their willingness to adopt collective mitigation behavior (e.g., joining a campaign to convince elected officials to take action to reduce global warming). Likewise, the message in Experiment 1 that emphasized the similarities between individual and collective behaviors had no effect on behavioral willingness. In contrast, in Experiment 2, the message explaining that reducing carbon emissions through collective behavior is beneficial for human health and the environment (Message-only condition) increased willingness to adopt collective mitigation behaviors (however, this was not the case in the Checklist + Message condition). These results are illustrated in the figure below.

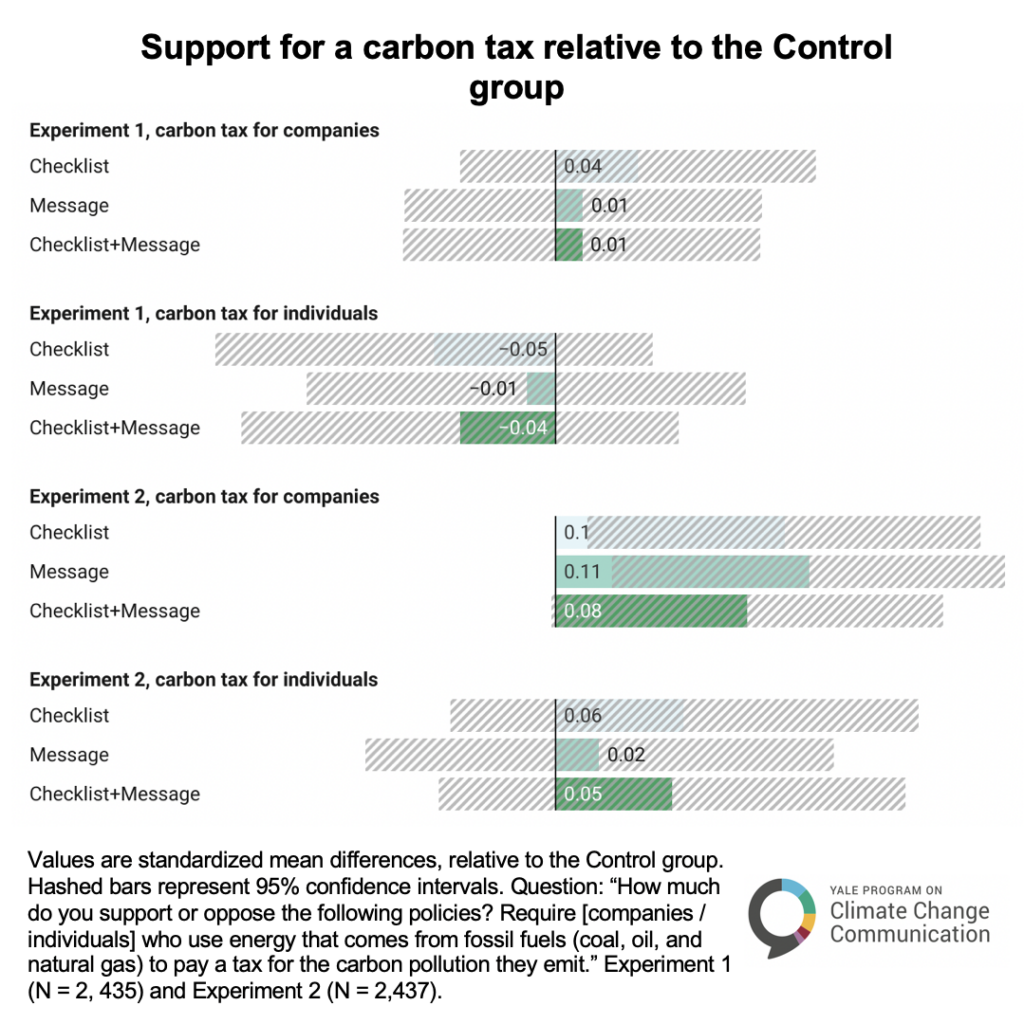

Second, looking at policy support, in Experiment 2, reminding people of the behaviors they had personally done in the past (Checklist condition) increased their support for a carbon tax paid by companies. Additionally, in Experiment 2, participants who read about the health and environmental benefits of collective climate action (Message-only condition) reported higher levels of support for a carbon tax paid by companies. However, neither of these effects were observed in the Checklist + Message Condition or in Experiment 1. In both experiments, support for a carbon tax that requires individuals, rather than companies, to pay, was not affected by reminding people of the climate-related behaviors they have done. Results are illustrated in the figure below.

These two experiments offer a new explanation for the absence of spillover effects on collective behavior. Specifically, we examined two possible mechanisms of behavioral spillover: the perception that one has already done enough, which is likely to reduce willingness to adopt collective behavior, and environmental identity, which is likely to increase willingness to adopt collective behavior. The overall results suggest that reminding people of the behaviors they have done in the past increases both their perception that they have already taken enough action and their environmental identity. This suggests that the simultaneous effects of mechanisms that promote both negative (“I already do enough”) and positive (“I am a pro-environmental person”) spillover might be responsible for the overall lack of spillover effects often found in the literature because, in effect, they cancel each other out.

These results suggest two takeaways for climate change communicators. First, reminding people of their personal mitigation behaviors does not reduce their willingness to perform collective behaviors. Instead, reminding individuals of the actions they have already taken can, depending on the message, increase support for a carbon tax paid by companies while having no negative effects on support for a carbon tax paid by individuals or on their willingness to take collective action. Second, directly targeting collective behaviors with a message about the benefits of those behaviors might be more effective than reminding people of behaviors they have already done, because the mechanisms of behavioral spillover of the latter are complex and may cancel each other out.

The full article is available here to those with a subscription to Energy Research & Social Science. If you would like to request a copy, please send an email to climatechange@yale.edu with the subject line: Request Spillover paper. A pre-publication version is also available here.