Climate Note · Jun 4, 2024

Who thinks people can affect what the government does about global warming?

By Nicholas Badullovich, Margaret Hilado, John Kotcher, Matthew Ballew, Kathryn Thier, Seth Rosenthal, Edward Maibach and Anthony Leiserowitz

Filed under: Audiences, Beliefs & Attitudes, Policy & Politics and Behaviors & Actions

Many Americans are worried about climate change, but research finds that relatively few engage in political action to influence policymakers. A key to collective action is a group’s sense of collective efficacy, the perception that a group of people can work together to achieve a specific outcome, for example, affecting federal government action on climate change.

Research has shown that higher collective efficacy is associated with greater participation in climate action; people with higher collective efficacy perceptions are more likely to engage in climate-related behaviors like attending a rally or protest. Thus, promoting perceptions of collective efficacy is likely to encourage people to join together to demand systemic change.

This analysis uses data from the Climate Change in the American Mind survey (October 2023; n = 1,033 U.S. adults) to explore perceptions of collective political efficacy, how confident Americans are that people like them can affect what the U.S. federal government does about global warming.

We first examine how perceived collective political efficacy has changed nationally since 2018. Then, we look at how this perception currently varies across demographic groups. Finally, we investigate the relationship between perceived collective efficacy and an important social cue: how often people hear others talk about global warming.

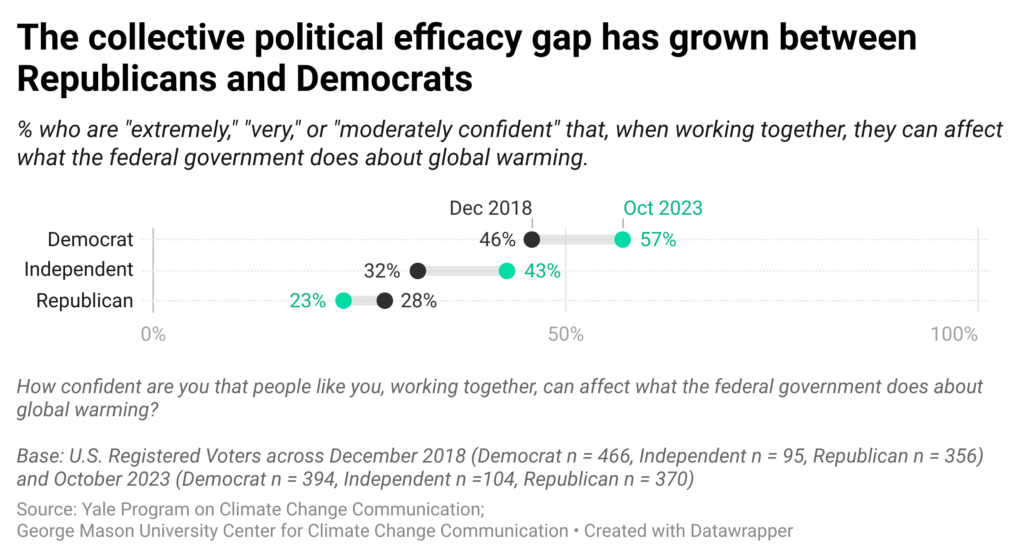

Recent trends in collective political efficacy on climate change

Overall, Americans’ perceptions of collective political efficacy have increased slightly since December 2018. In 2018, 38% of Americans felt at least “moderately confident” that they could affect what the federal government does about global warming. This increased to 43% of Americans by October 2023 (a 5 percentage point increase over five years).

This trend differed, however, by political party. Among registered voters, Democrats (+11 percentage points from 46% in 2018 to 57% in 2023) and Independents (+11 percentage points from 32% in 2018 to 43% in 2023) experienced a large increase in collective political efficacy, whereas Republicans saw a small, but not statistically significant decrease (-5 percentage points from 28% in 2018 to 23% in 2023).

Additionally, the gap in collective political efficacy between Democrats and Republicans has increased over time, more than doubling from a 16 percentage point difference in 2018 to a 34 percentage point difference in 2023.

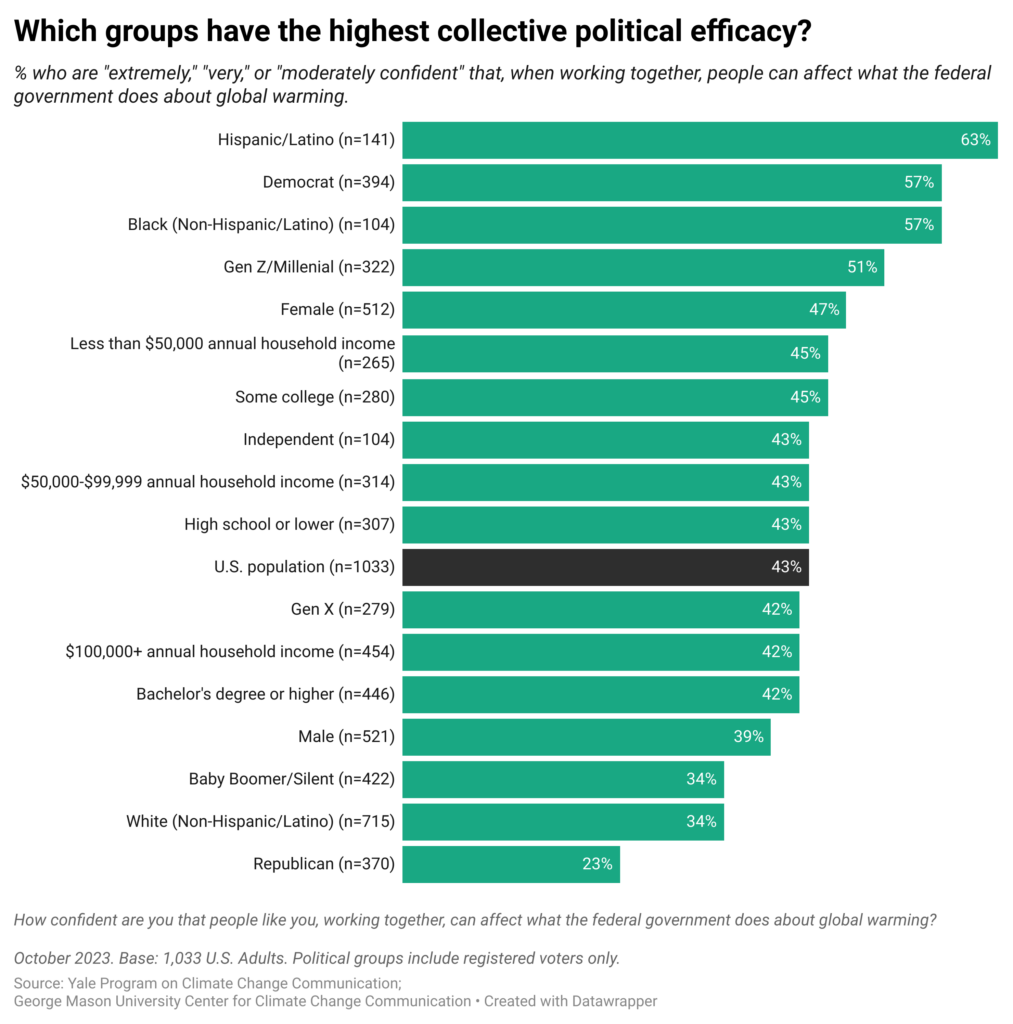

Current demographic differences in collective political efficacy on climate change

As of October 2023, the demographic groups with the highest levels of perceived collective political efficacy included Hispanics/Latinos, Black/African Americans, Democrats, and Gen Z/Millennials, with half or more in each of these groups at least “moderately confident” that they can affect what the federal government does about global warming. The groups with the lowest perceived collective political efficacy included Republicans, White Americans, Baby Boomers/Silent Generation, and males, with fewer than 40% of each group being at least “moderately confident.”

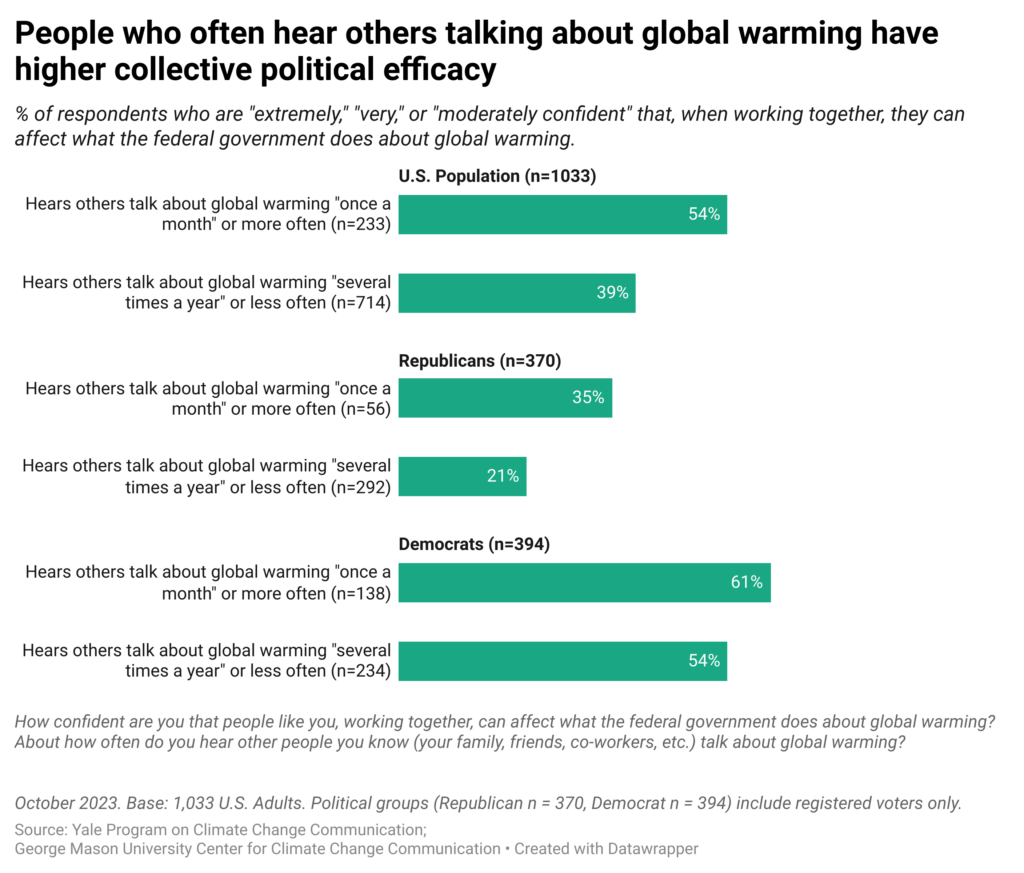

Do people who hear others talk about global warming have higher collective political efficacy on climate change?

Research has shown that cues from one’s social environment (e.g., hearing others discuss global warming) are positively associated with efficacy beliefs. For example, when people hear their family and friends talking about global warming, it can convey a social norm that others care about the issue. Here, we explore the relationship between hearing people discuss global warming and perceived collective political efficacy.

Americans who hear others talk about global warming at least once a month have higher levels of perceived collective political efficacy (54%) than those who hear others talk about global warming less often (39%). This is true of both Republicans and Democrats; however, the relationship is stronger among Republicans. The difference in perceived collective political efficacy between Republicans who hear others talk about global warming more often (35%) versus less often (21%; a 14 percentage point difference) is greater than the difference in efficacy between Democrats who hear others talk about global warming more often (61%) versus less often (54%; a 7 percentage point difference). While we cannot determine causal relationships from this analysis, this is consistent with past research that suggests conservatives’ views on climate change may be more sensitive to social influence than liberals.

Key takeaways

Many Americans are at least “moderately confident” that people like them, working together, can affect what the federal government does about global warming, but some groups have higher levels of perceived efficacy than others (e.g., Hispanic/Latinos, Black Americans, and Democrats). Efficacy beliefs can motivate people to engage in climate actions, including political behavior like voting or adopting pro-environmental behaviors.

Communication can be used to strengthen these beliefs among key audiences, although the specific pathways to these outcomes may require additional research. Social cues also matter, especially among Republicans. Efforts to cultivate more conversations about climate change may have the added benefit of increasing perceived collective political efficacy, although more research is needed to establish whether there is a causal connection between discussion about global warming and collective efficacy.

Methods

The results of this report are based on 2018 & 2023 data from two waves of the Climate Change in the American Mind survey – a nationally representative survey of U.S. public opinion on climate change conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication. Data were collected in December 2018 (n = 1,114) and October 2023 (n = 1,033) using the Ipsos KnowledgePanel®, a representative online panel of U.S. adults ages 18 and older. Questionnaires were self-administered online in a web-based environment.

Data for each survey wave were weighted to align with demographic parameters in the United States. Following Pew Research Center’s approach, generational cohort and year of birth were calculated based on the age of respondents at the time of data collection (Gen Z: 1997-2012; Millennial: 1981-1996; Gen X: 1965-1980; Baby Boomer: 1946-1964; and Silent Generation: 1928-1945). Because generational cohort classification was based on respondents’ age at the time they took the survey (rather than birth year, which was not known), some respondents on the cusp of two generations may be miscategorized. We are unable to describe the views of other racial/ethnic groups (including Asian Americans, Native Americans, and adults who identify with 2+ races) because of sample size limitations.

References to Republicans and Democrats, and Independents include respondents who initially identify as either a Republican or Democrat, as well as those who initially identify as Independent or members of another party, but say they “are closer to” one of the two major parties in a follow-up question (i.e., “leaners”). Respondents who initially identify as Independent or members of another party who say they lean toward “neither” the Republican nor Democratic party are classified as (non-leaning) Independents.

Group differences were tested for statistical significance using the weighted proportions and unweighted sample sizes of each group. The average margin of error at the 95% confidence interval for each wave of data is +/- 3 percentage points. Data tables document for details and margins of error for subgroups are available here.