Peer-Reviewed Article · Jan 23, 2025

Americans’ support for climate justice

By Jennifer Carman, Danning (Leilani) Lu, Matthew Ballew, Joshua Low, Marija Verner, Seth Rosenthal, Kristin Barendregt-Ludwig, Gerald Torres, Michel Gelobter, Kate McKenney, Irene Burga, Mark Magaña, Saad Amer, Romona Taylor Williams, Montana Burgess, Grace McRae, Annika Larson, Manuel Salgado, Leah Ndumi Kioko, Jennifer Marlon, Kathryn Thier, John Kotcher, Edward Maibach and Anthony Leiserowitz

Filed under: Beliefs & Attitudes, Policy & Politics and Behaviors & Actions

We are pleased to announce the publication of a new article, “Americans’ support for climate justice,” in the journal Environmental Science & Policy.

Climate change is unfair. While it harms people from all walks of life, the groups and nations that bear the least responsibility for causing climate change are disproportionately burdened with its impacts. These inequalities stem from many historical factors, are deeply rooted in social systems, and continue to affect individuals’ lives. For example, the historically racist housing investment policy of redlining in the U.S. is linked to disproportionate harms to non-White populations through greater exposure to environmental hazards like heat and air pollution. Moreover, investments in climate change solutions, such as disaster relief and renewable energy, tend to disproportionately benefit people and communities who are already advantaged.

The goals of climate justice are to reduce these unequal harms of climate change, produce equitable benefits from climate solutions, and include affected communities in the decision-making process. Achieving climate justice requires sustained, focused effort from institutions and policymakers. Understanding public support for climate justice and avenues for political action can help achieve it.

In collaboration with climate justice advocates and experts in the U.S. and Canada, we measured and explored predictors of Americans’ climate justice beliefs and intentions to engage in related behaviors as part of the Climate Change in the American Mind survey (n = 1,011).

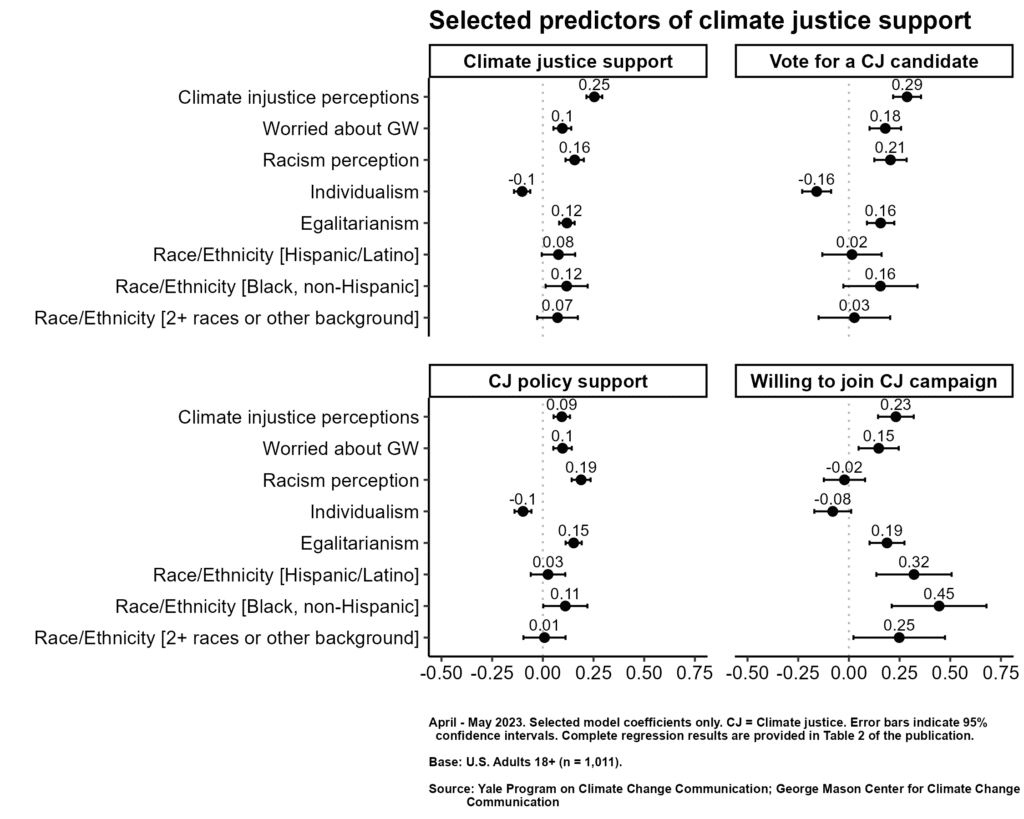

We find that only about one-third of Americans have heard of climate justice, but after reading a description of its goals, many more Americans support climate justice (53%) than oppose it (19%). We find that people who perceive climate injustice (i.e., people who think climate change harms some groups unfairly) are more likely to support climate justice; express willingness to vote for a candidate who supports climate justice; support climate justice policy; and express willingness to join a climate justice campaign. We also find that people of color and/or who think racism is a problem are more likely to support climate justice and engage in climate justice action. Finally, we find many variables that predict political engagement with climate change more broadly – such as worry about climate change and cultural worldviews – also predict support for climate justice. This suggests that people who are more concerned about climate change are also concerned about climate justice once they learn about it. However, most people who are concerned about climate change are not familiar with climate justice goals.

Our study suggests a need to build public awareness of the term “climate justice,” the disproportionate harms of climate change, and how climate justice initiatives will address these harms. Organizers have been building awareness of, and capacity for, environmental and climate justice in disproportionately affected communities for decades, and our study suggests that there are potentially deep wells of additional support to be tapped at the national level. Based on these findings, our partners offer the following recommendations:

Existing climate justice efforts should incorporate climate justice communication more explicitly, and they need resources to do so. Although current awareness of climate justice is low, many Americans are receptive to learning about and supporting climate justice goals. These efforts may include direct outreach, as well as formal and informal education from organizers and public institutions such as schools and libraries, companies, and governments.

Communication about climate justice should describe specific ways that climate change harms some people more than others, as well as the practical benefits of climate justice initiatives. For example, investments in infrastructure for vulnerable communities can reduce everyone’s risks from climate change impacts such as flooding. Moreover, many existing policies that promote climate justice – such as green job training and reskilling programs, transitioning to renewable energy, and home weatherization – are already popular among the U.S. public, so linking climate justice concepts to these benefits may build support.

There are different audiences for climate justice communication. On the one hand, communities of color, and those who are concerned about racial justice, are more supportive of climate justice but are not necessarily more aware of it. Educating this audience about climate justice is an important priority. On the other hand, audiences that are less concerned about climate change might dismiss the term “climate justice” altogether, even though many people in this group may benefit from climate justice initiatives such as job creation and pollution reduction. In these cases, it may be preferable to avoid direct usage of the term “climate justice” and talk more about local harms and benefits. For all audiences, stories and testimonials from people in affected communities can make the issue more relatable and urgent.

Finally, climate justice engagement at all levels should meaningfully incorporate affected communities in decision-making. Community trust is crucial to supporting climate justice, both for decision-makers and researchers. Our study illustrates how researchers can incorporate practitioner perspectives in national and international studies on climate justice, but efforts should not end there. Connecting experts to affected communities is key.

The full article is available here for those with a subscription to Environmental Science & Policy, and a public postprint is available here on the Open Science Framework.

The authors are grateful to Andrea Aguilar, Sha Merirei Ongelungel, Karina Sahlin, and Cristian Sanchez of the Digital Climate Coalition; Makeda Fekede of the Sierra Club; Denise Abdul Rahman and Thomas Minor of the Chisholm Legacy Project; and Astrid DuBois and Dana Johnson of WE ACT for Environmental Justice for providing additional input and guidance in the development of this project.