Peer-Reviewed Article · Apr 3, 2024

Climate change belief systems across political groups in the United States

By Sanguk Lee, Matthew Goldberg, Seth Rosenthal, Edward Maibach, John Kotcher and Anthony Leiserowitz

Filed under: Beliefs & Attitudes

We are pleased to announce the publication of a new article, “Climate change belief systems across political groups in the United States” in the journal PLOS ONE.

Beliefs and attitudes are connected to each other, forming a network called a belief system. Investigating the structure of climate change belief systems provides several benefits. First, by identifying elements at the center of the system, it can help identify intervention points that might increase the effects of climate messages. Second, this approach helps us understand how people in different political groups organize their beliefs and attitudes.

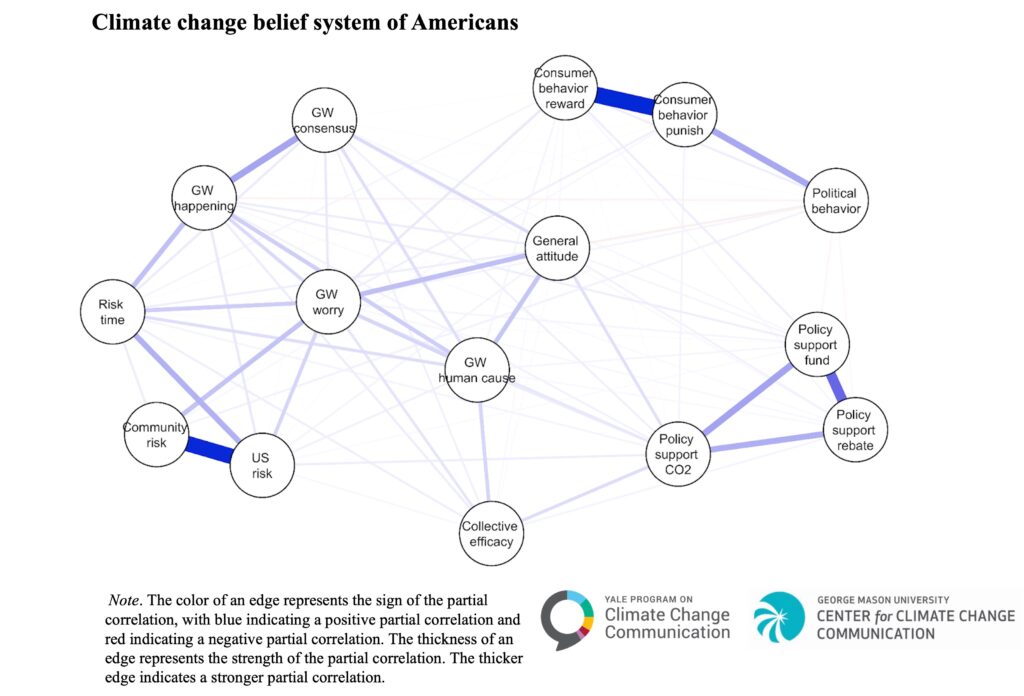

Applying network analysis to fifteen waves of our Climate Change American Mind survey data, we constructed a map of Americans’ climate change belief systems. The belief system includes fifteen elements, including beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors related to climate change. The connections between variables are drawn based on partial correlations.

First, we investigated which elements are positioned at the center of Americans’ climate change belief systems. Multiple metrics including betweenness, closeness, and strength centralities indicate that worry about global warming is the central element in these belief systems. This indicates that worry plays a significant role in connecting various psychological elements, including beliefs, risk perceptions, attitudes, policy support, and behaviors. Moreover, changes in the level of worry have a greater potential than other elements to have cascading impacts on other psychological and behavioral elements within the belief system.

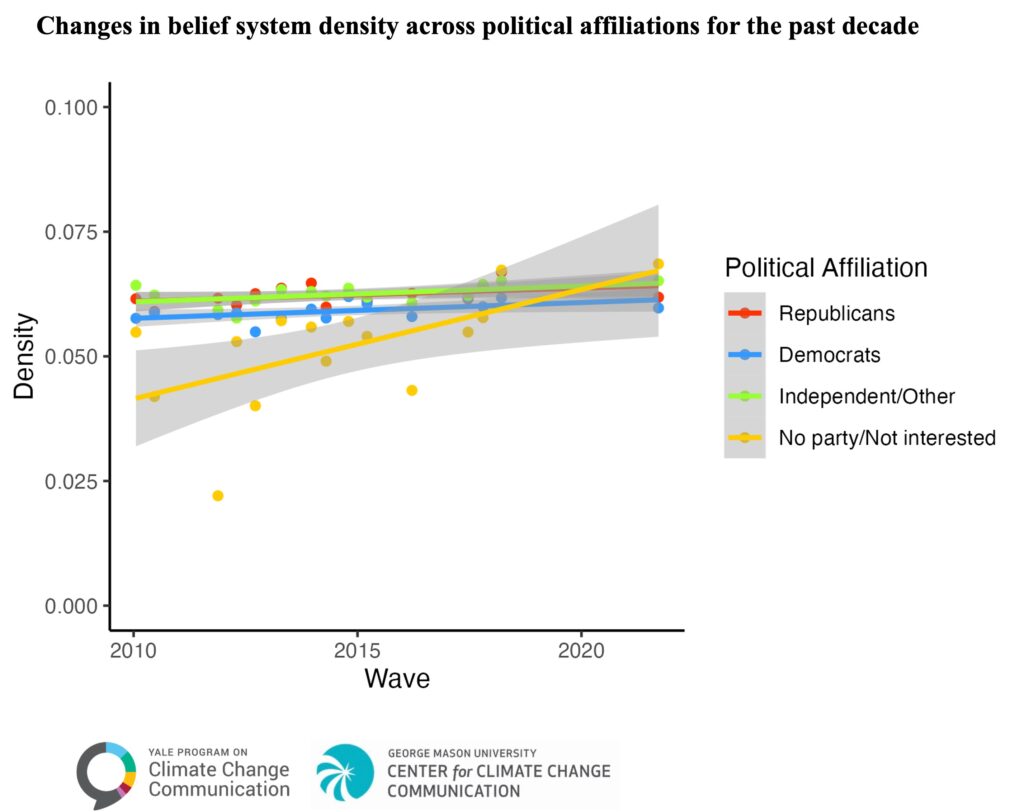

Second, we examined how the strength of connections (i.e., density) among these belief elements changed over the past decade within different political groups. We found that there was a significant increase in the density of the No party/Not Interested (in politics) group, whereas the density of groups with Democratic, Republican, and Independent/Other political affiliations remained relatively stable over time.

We also compared the structures of belief systems across political groups and found that despite Republicans’ lower levels of pro-climate beliefs and attitudes in comparison to Democrats, the underlying structure that governs how individuals from both groups organize their belief systems is not markedly different. So, for example, worry about climate change is the central element in the structure of climate change belief systems among both Democrats and Republicans, even though Republicans worry less about climate change, on average, than do Democrats.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that belief system analysis can enrich our understanding of how different populations think and feel about climate change and suggest more effective communication strategies.

The full article with many other results is available here.