Climate Note · May 8, 2019

Changes in Awareness of and Support for the Green New Deal: December 2018 to April 2019

By Abel Gustafson, Seth Rosenthal, Parrish Bergquist, Matthew Ballew, Matthew Goldberg, John Kotcher, Anthony Leiserowitz and Edward Maibach

Filed under: Policy & Politics

Republican support for the Green New Deal decreased dramatically in four months.

From December 2018 to April 2019, public familiarity with – and support for – the Green New Deal shifted dramatically. In particular, Republicans now say they are both much more familiar with the proposal and much more opposed to it. Opposition to the Green New Deal is especially strong among those Republicans who have heard “a lot” about it. In contrast, support among Democrats has remained high regardless of how much they have heard about it. Here, we summarize this rapid political polarization on the Green New Deal and discuss how it may relate to politicized media coverage.

Awareness

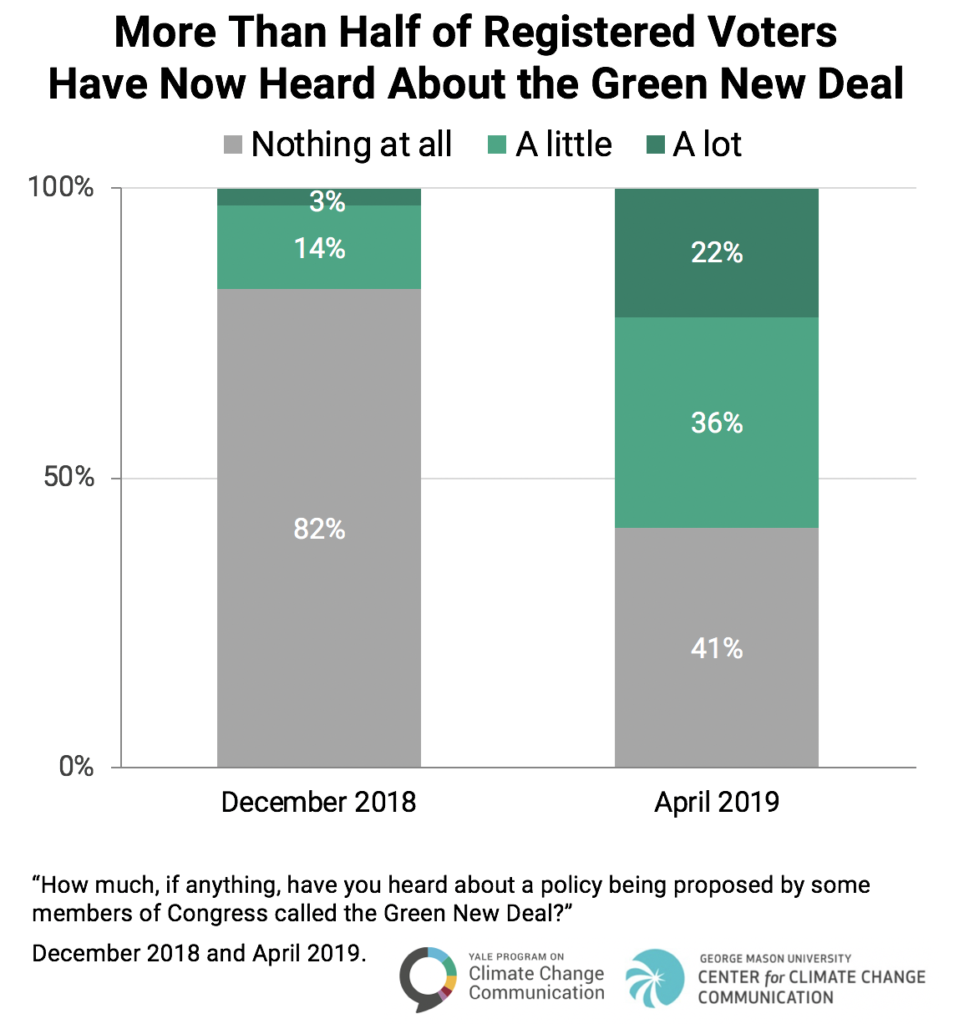

In December 2018, the Green New Deal was just entering the national spotlight – propelled by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and a wave of grassroots activism. In a nationally representative survey we conducted in December, we found that most registered voters (82%) were unaware of the Green New Deal, having heard “nothing at all” about it.

Our April 2019 survey, however, found that many more registered voters were now aware of the Green New Deal. For example, the proportion of registered voters who had heard at least “a little” about the Green New Deal more than tripled from 17% to 59%. The proportion who had heard “nothing at all” decreased by half – from 82% to 41%.

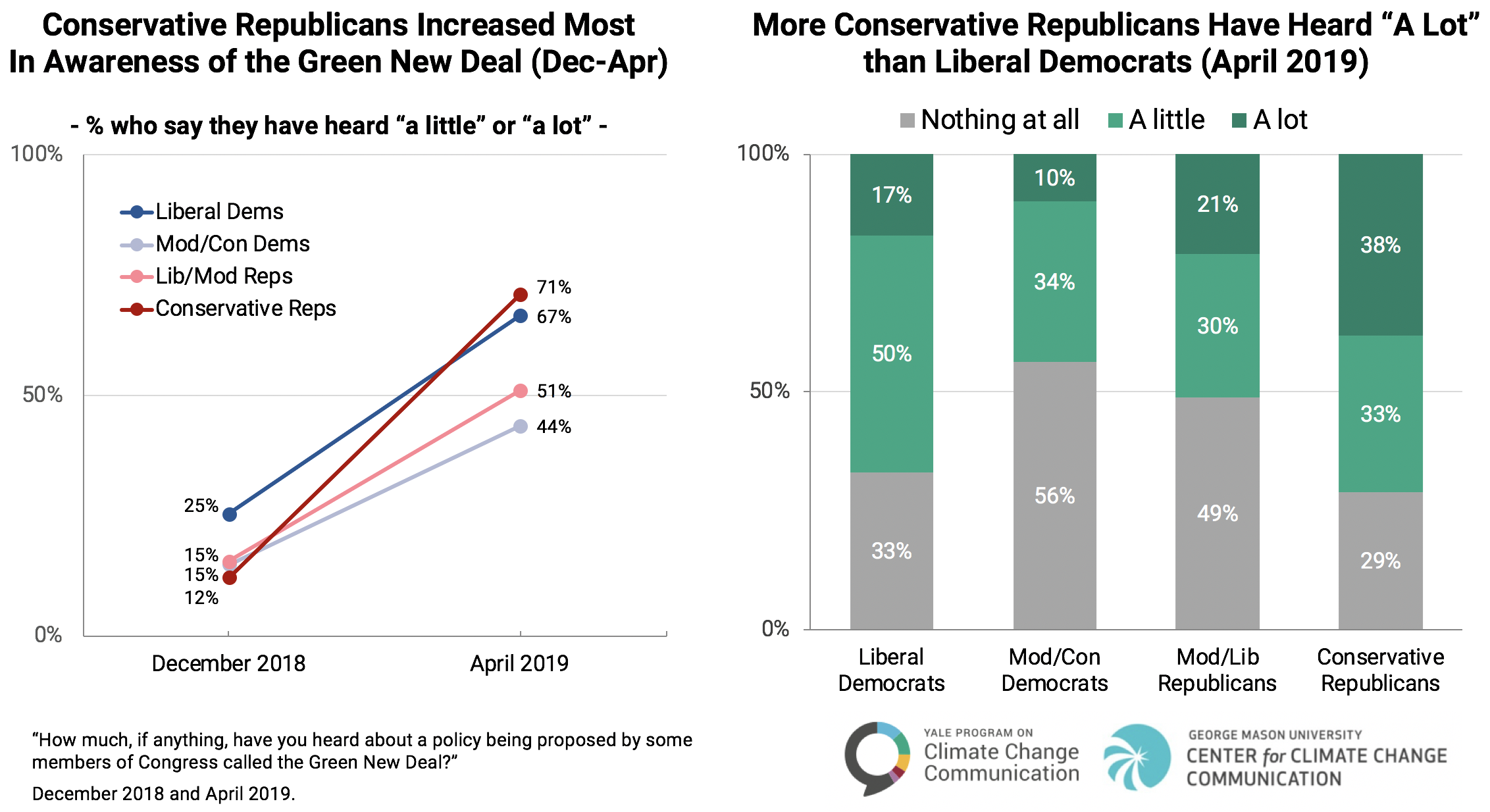

This increase in public awareness, however, differed sharply by party and political ideology. Awareness of the Green New Deal increased the most among conservative Republicans (+59 percentage points), with smaller increases among liberal Democrats (+41 points), liberal/moderate Republicans (+36 points) and moderate/conservative Democrats (+29 points). As of April 2019, the proportion of conservative Republicans who had heard “a lot” about the Green New Deal (38%) was twice that of liberal Democrats (17%).

Support for the Green New Deal

In our December 2018 survey, we provided a one-paragraph description of the goals of the Green New Deal:

“Some members of Congress are proposing a “Green New Deal” for the U.S. They say that a Green New Deal will produce jobs and strengthen America’s economy by accelerating the transition from fossil fuels to clean, renewable energy. The “Deal” would generate 100% of the nation’s electricity from clean, renewable sources within the next 10 years, upgrade the nation’s energy grid, buildings and transportation infrastructure, increase energy efficiency, invest in “green” technology research and development, and provide training for jobs in the new “green” economy. How much do you support or oppose this idea?”

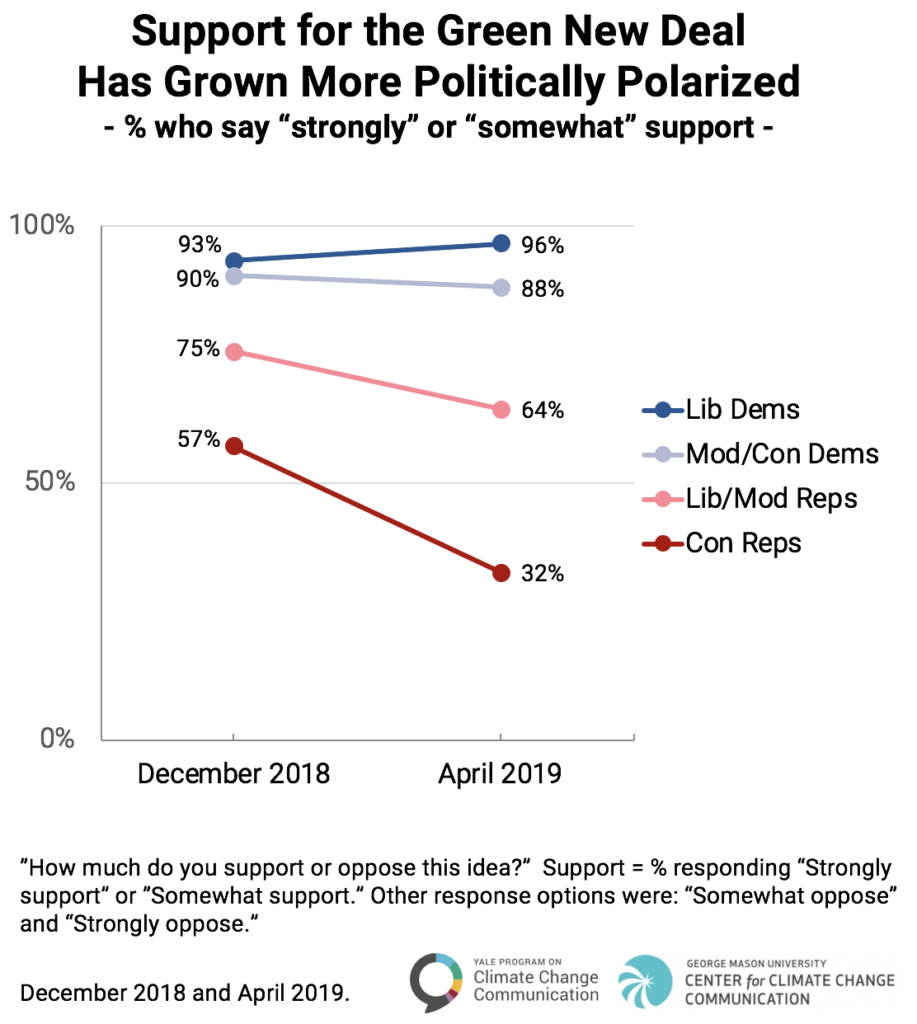

In our December survey, we found that after that introduction, 81% of registered voters – including 64% of all Republicans – supported the Green New Deal.

By April 2019, however, the Green New Deal had become much more politically polarized. Support for the Green New Deal remained high among Democrats from December 2018 to April 2019, while support among Republicans dropped dramatically (-20 percentage points), including among conservative Republicans (-25 points) and liberal/moderate Republicans (-11 points).

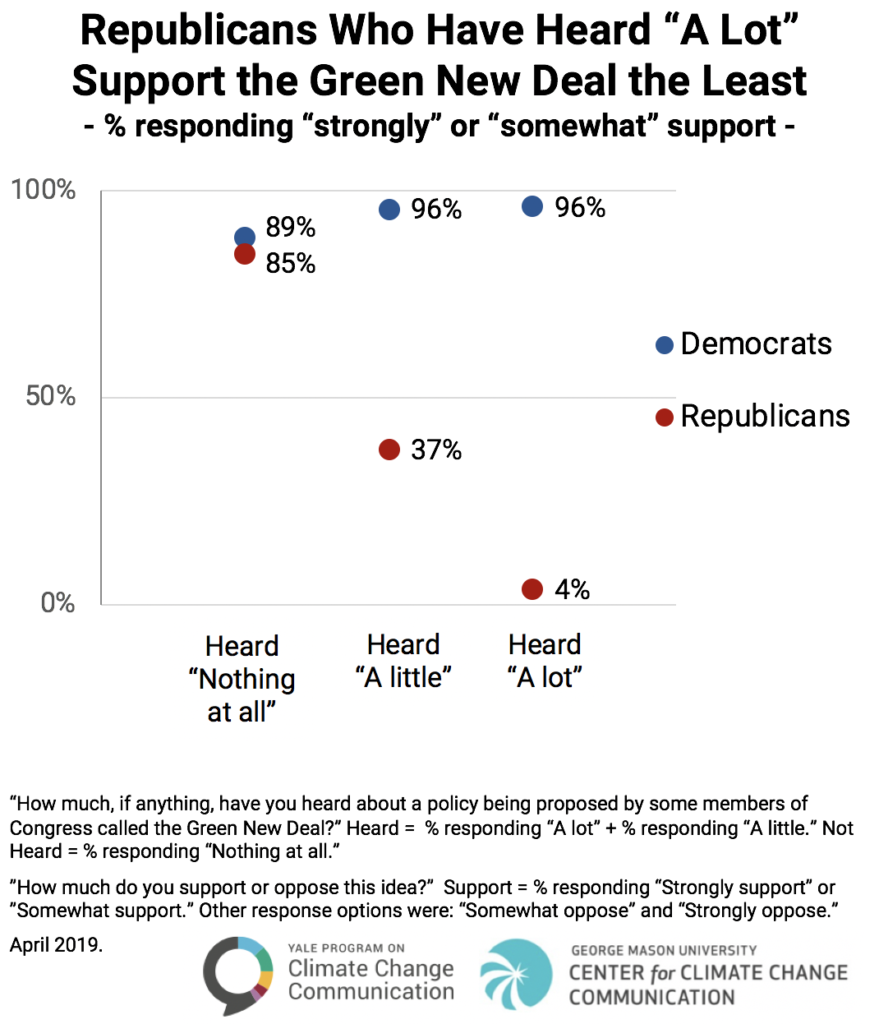

We also find a substantial interaction between awareness, support, and political party in our April survey data. Democrats who have heard “a lot” about the Green New Deal are 7 percentage points more supportive of the proposal than are Democrats who have heard “nothing at all” (96% vs. 89%, respectively). By contrast, Republicans who have heard “a lot” about the Green New Deal are 81 percentage points less supportive of the proposal than are Republicans who have heard “nothing at all” (85% vs. 4%, respectively).

In other words, those Republicans who have heard the most about the Green New Deal are the least likely to support it. This finding raises a key question, then, about where Republicans have learned about the Green New Deal, and how those sources of information affected their opinions.

The Green New Deal has been covered extensively by conservative media. For example, in the week leading up to the March 26th Senate vote on the Green New Deal resolution, Fox News ran more prime-time segments about it than CNN and MSNBC combined.

Further, our April 2019 survey found that 82% of Republicans who watch, read, or listen to Fox News more than once per week have heard about the Green New Deal – a 64-point increase since December. Republicans who watch Fox News less often are substantially less familiar with the Green New Deal.

Similarly, support for the Green New Deal is lower among Republicans who watch Fox News more frequently than it is among Republicans who watch it less often. In our April survey, of those Republicans who watch Fox News more than once per week, only about one in five (22%) support the Green New Deal – a decrease of 32 points from December. By contrast, of those Republicans who watch Fox News once per week or less, over half (56%) supported the Green New Deal in April – a relatively smaller decrease of 15 points since December.

This pattern of greater awareness of and less support for the Green New Deal among frequent Fox News-watching Republicans may be due to what has previously been called “The Fox News Effect” – the contention that Fox News is a driving force of political polarization in America. It is also possible, however, that Republicans who watch Fox News more frequently are more politically engaged than other Republicans, and thus are also more exposed to other sources of information that may have influenced their opinions about the Green New Deal.

Importantly, however, these frequent Fox News viewers constitute only 35% of Republican registered voters. That is, a majority (65%) do not watch Fox News more than once per week, and 56% of those Republicans who watch Fox News less frequently still support the Green New Deal.

Overall, these shifting views of the Green New Deal are an example of how quickly partisan polarization can develop over a short period of time at the national level.

Our April 2019 survey also measured Americans’ opinions about the economics of the Green New Deal and preferences for its scope, as well as many other aspects of climate change and climate policy. Our forthcoming “Politics and Policy” report (May 2019) will describe how public opinion on these matters vary across the political spectrum. To receive the report in your inbox, sign up for our email list here:

Methods

These data were produced by the bi-annual Climate Change in the American Mind survey conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication.

Surveys were conducted using the Ipsos KnowledgePanel®, a representative online panel of U.S. adults (18+), from November 28 to December 11, 2018 and from March 29 to April 9, 2019. All questionnaires were self-administered by respondents in a web-based environment. This report includes the registered voters (2018 N = 966; 2019 N = 1,097), from the full samples (2018 N = 1,114; 2019 N = 1,291). Unweighted base sizes for the political subgroups by year are as follows: 2018 Democrats n = 466 (liberal Democrats n = 295, moderate/conservative Democrats n = 168), 2018 Republicans n = 356 (conservative Republicans n = 238, moderate/liberal Republicans n = 116). 2019 Democrats n = 475 (liberal Democrats n = 264, moderate/conservative Democrats n = 209), 2019 Republicans n = 488 (conservative Republicans n = 320, moderate/liberal Republicans n = 165).

References to Republicans and Democrats throughout include respondents who initially identify as either a Republican or Democrat, as well as those who do not initially identify as Republicans or Democrats but who say they “are closer to” one party or the other (i.e., “leaners”) in a follow-up question. Average margin of error for both the full sample and registered voter subset: +/- 3 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. The margin of error for each political subgroup is larger. Bases specified are unweighted, but percentages are weighted to align with U.S. Census parameters. For tabulation purposes, percentage points are rounded to the nearest whole number. As a result, percentages in a given chart may total slightly higher or lower than 100%. Additionally, summed response categories (e.g., “strongly support” + “somewhat support”) are rounded after sums are calculated (e.g., 25.3% + 25.3% = 50.6%, which, after rounding would appear in a chart as 25% + 25% = 51%).