Climate Note · Mar 21, 2024

The attitude-behavior gap on climate action: How can it be bridged?

By Matthew Ballew, Jennifer Carman, Marija Verner, Seth Rosenthal, Edward Maibach, John Kotcher and Anthony Leiserowitz

Filed under: Audiences, Beliefs & Attitudes and Behaviors & Actions

There are many ways that people can take action to reduce climate change, from personal behaviors like eating a more plant-rich diet to collective behaviors like political activism. Political activism (such as contacting government officials to express support for pro-climate policies) is one of the most significant ways to influence government policy-making.

However, relatively few Americans engage in political actions to limit global warming, such as signing petitions, volunteering, or contacting government officials. While majorities think that global warming should be a high government priority and support various climate policies, there is a discrepancy between the public’s attitudes about climate action and their behaviors or actions that support it. Research that offers insights into this “attitude-behavior gap” can identify opportunities to reduce the gap and thereby strengthen both public and political will.

In this analysis, we investigate the attitude-behavior gap on political climate action using the six most recent waves of our Climate Change in the American Mind surveys spanning 2021-2023 (n = 6,190 U.S. adults). We focus on four political actions: (1) signing a petition about global warming, either online or in person; (2) donating money to an organization working on global warming; (3) volunteering time to an organization working on global warming; and (4) writing letters, emailing, or phoning government officials about global warming. Respondents were asked about their willingness to engage in each of the behaviors and, separately, how many times they had done them over the prior 12 months. We compare the gap between willingness to engage versus self-reported behavior across all four actions, and explore differences between Americans who are willing and active and those who are willing but inactive.

Results

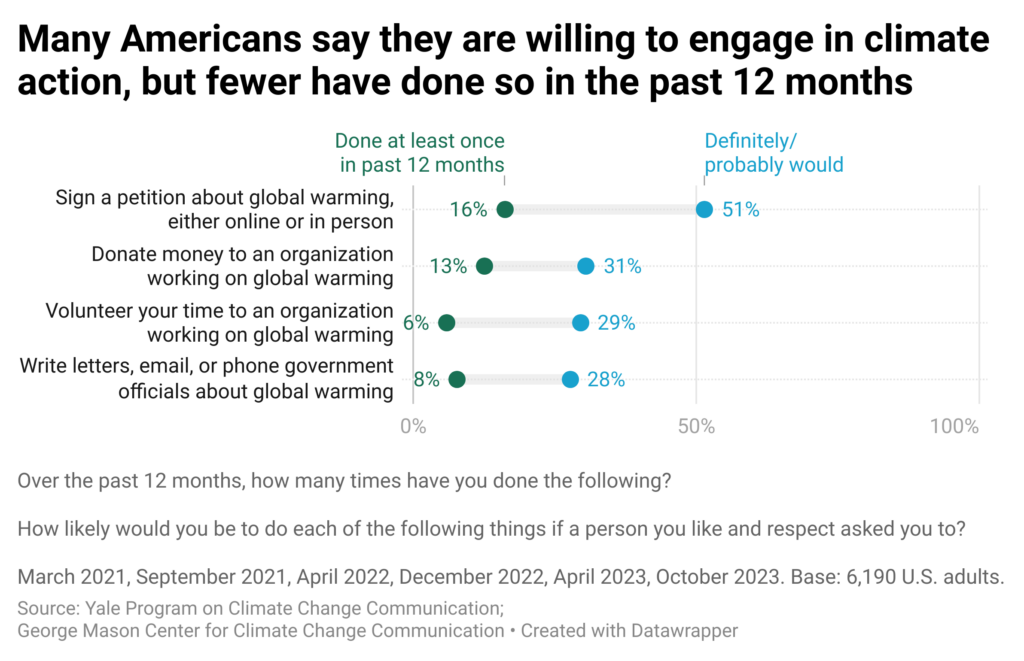

Many Americans say they “definitely” or “probably” would engage in political climate action if someone they like and respect asked them to. These actions include signing a petition about global warming, either online or in person (51%), donating money to an organization working on global warming (31%), volunteering time to an organization working on global warming (29%), or contacting government officials about global warming (28%). However, fewer Americans report engaging in these behaviors at least “once” in the prior 12 months (signing a petition, 16%; donating money, 13%; volunteering, 6%; contacting government officials, 8%).

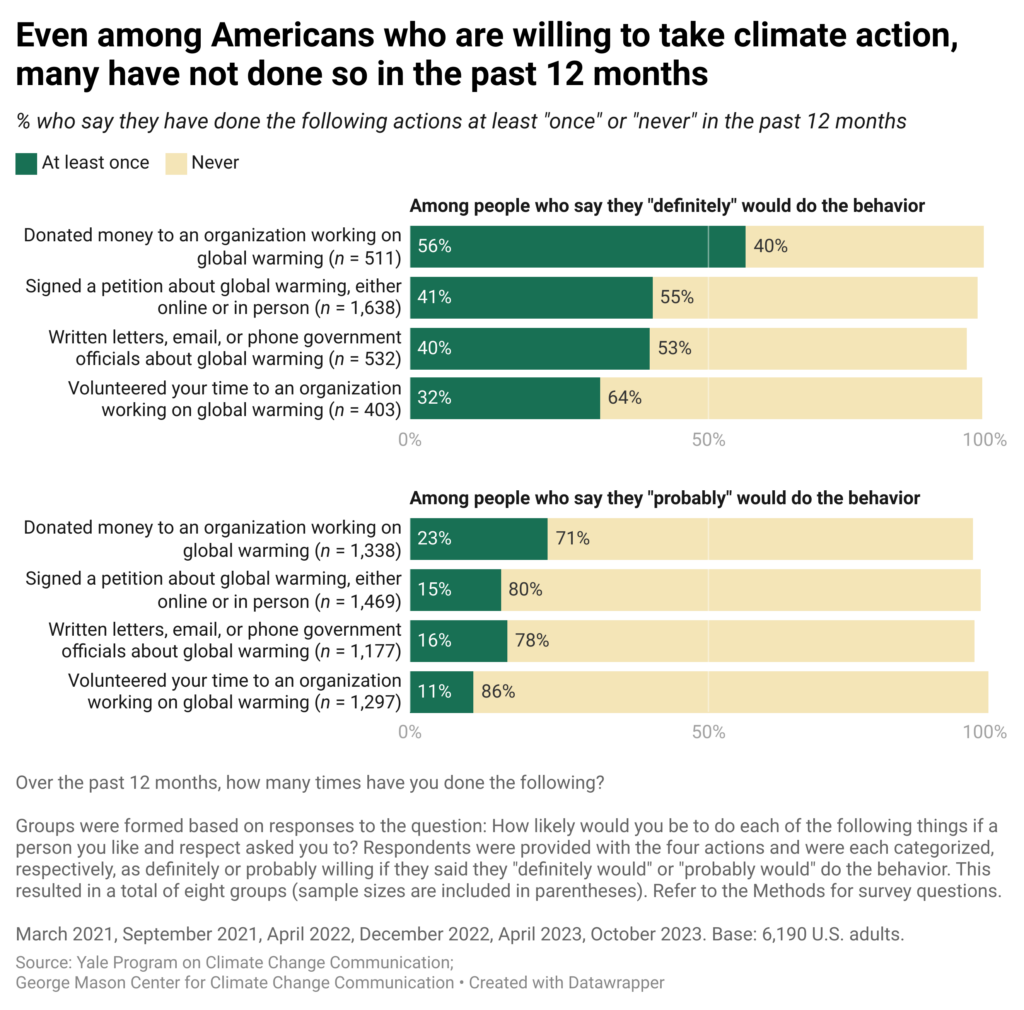

We find that Americans who are the most willing to engage in each climate action are also the most likely to actually do so. For instance, among the people who say they “definitely” would donate money to an organization working on global warming, 56% report donating money at least “once” in the past 12 months, while 40% report “never” doing so. By contrast, among those who say they “probably” would donate money, only 23% report donating money at least “once” over the past 12 months, while most (71%) report “never” doing so. However, there are gaps even among the people who are most willing to act. For each of the other three actions, half or more Americans who say they “definitely” or “probably” would do the specific behavior in question say they have “never” done it over the past 12 months.

To understand the factors that may contribute to the attitude-behavior gap on climate action, we focused on the 30% of Americans who say they “definitely would” engage in at least one of the four behaviors. Half of this group (i.e., 15% of Americans) report doing at least one of the behaviors “once” or more often in the past 12 months (“Definitely willing and active”), while the other half have not (“Definitely willing but inactive”). We compared these groups to all other Americans and explored differences in communication behaviors, perceptions of social norms, and collective efficacy beliefs.

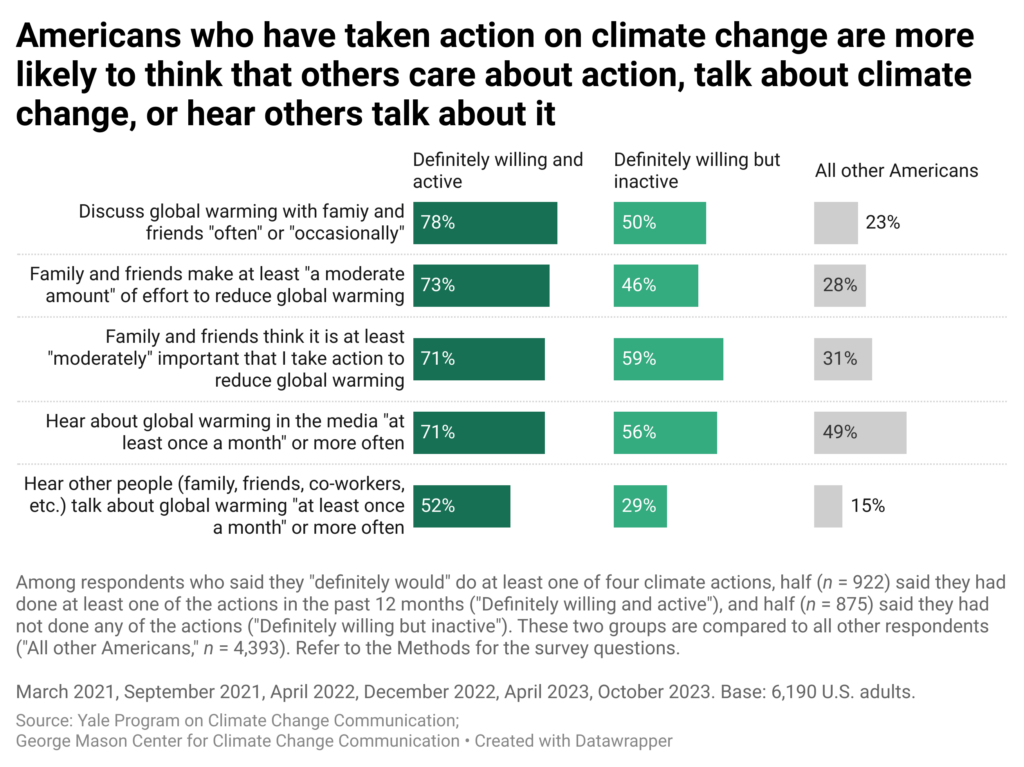

The “Definitely willing and active” are more likely than both the “Definitely willing but inactive” and other Americans to discuss global warming with family and friends (respectively, 78%, 50%, and 23%), hear about global warming in the media (71%, 56%, and 49%), or hear other people talk about global warming (52%, 29%, and 15%). Additionally, the “Definitely willing and active” are more likely to perceive social norms supportive of climate action, including descriptive norms (i.e., how much of an effort family and friends make to reduce global warming; 73%, 46%, and 28%) and injunctive norms (i.e., how important it is to family and friends that you take action to reduce global warming; 71%, 59%, and 31%).

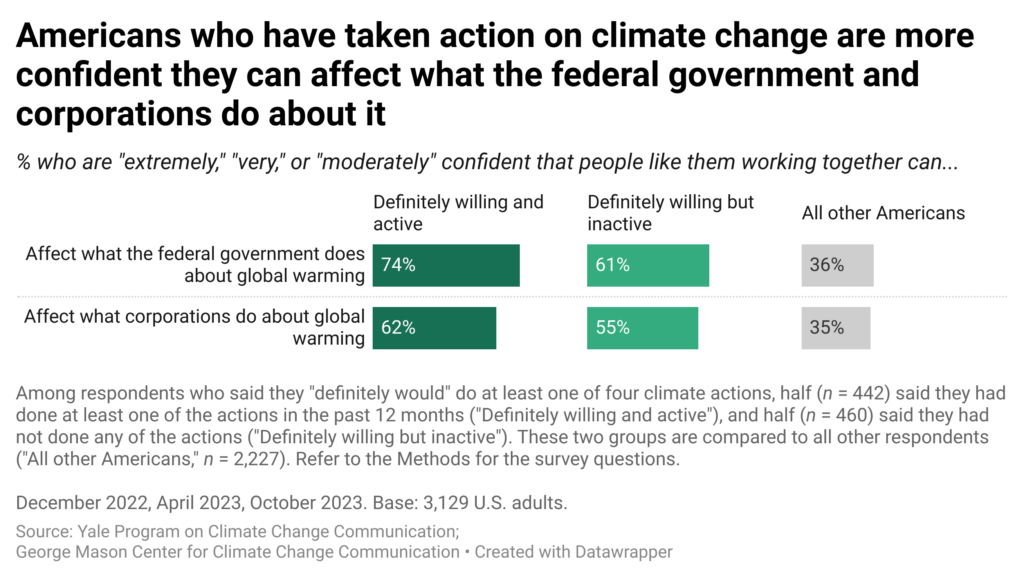

The “Definitely willing and active” also report stronger collective efficacy beliefs than both the “Definitely willing but inactive” and other Americans. They are more confident that people like them, working together, can affect what the federal government does about global warming (respectively, 74%, 61%, and 36%) or what corporations do about it (62%, 55%, and 35%).

We find that there is an attitude-behavior gap on climate action: many Americans are willing to engage in political actions to address climate change, but fewer report doing so. Even among the people who are most willing to act, many say they haven’t done so in the prior year. There are also important differences between people who are active and those who are not, including in perceived social norms, communication behaviors, and collective efficacy beliefs. We have found similar patterns among the Alarmed, or those who are most worried about climate change: Americans who are Alarmed and actively engaged in climate issues are more likely than those who are not active to talk about climate change and express a sense of collective efficacy. While we cannot determine causal relationships from these findings, the results align with previous research on the drivers of political action on climate change and provide implications for bridging the attitude-behavior gap.

How can the attitude-behavior gap on climate action be bridged?

In this analysis, 30% of Americans said they “definitely would” do at least one of four political actions to address climate change – over 100 million people who are very willing to engage. However, the barriers to climate action are complex, including psychological, social, and structural/logistical factors. For political actions such as contacting government officials, we have found that the most frequent barrier for registered voters is that no one has ever asked them to do it. In addition, many say that it wouldn’t make any difference, they are not activists, they don’t know who to contact, or they wouldn’t know what to say. Based on previous research and the results here, below are some ways to address these barriers and encourage climate action:

- Ask people directly to get involved. Interpersonal communication can have a powerful influence on people’s beliefs and behavior. People can be asked directly through digital means or face-to-face (e.g., by community members, opinion leaders), which may be especially effective at promoting change. For instance, research has found that face-to-face discussions (e.g., deep canvassing) about political issues leads to enduring changes in attitudes and behavior.

- Make it easy and show people how to do it. Many people say they don’t have the time or information about how to act. Providing convenient opportunities that are quick to perform and include easy-to-follow steps (e.g., flow charts, infographics) can reduce time and knowledge barriers to engagement.

- Provide options and describe their benefits. There are many ways that people can reduce climate change. Providing a short menu of options can help people choose the actions that best suit them and may also help to reduce the barrier of feeling like “I am not an activist.” Additionally, showcasing the benefits of action can encourage people to choose behaviors that align with their personal values and interests (i.e., what they care most about).

- Strengthen perceptions of collective efficacy. The belief that people can collectively make a difference on climate change is a key motivator of climate action. To address the perceived barrier that “it wouldn’t make any difference,” communicators can remind people that every individual action matters. For instance, by highlighting success stories and the positive effects of taking action, individuals may feel more confident and inspired to act themselves.

- Encourage talking about climate change and provide guidance. Discussing climate change with others is a significant climate action that everyone can engage in. Also, research shows that increased discussions about climate change can strengthen acceptance of climate science. Researchers have proposed that “talking about climate change amplifies and normalizes it within networks, making people more likely to act.” Providing guidance on how to talk about climate change and encouraging discussions may support more public engagement.

- Amplify pro-climate social norms and diverse public voices. Social norms can powerfully shape people’s behavior and social intervention strategies are among the most effective ways to promote pro-climate behavior. Communicating social norms may also reduce identity-related barriers to action and show people there are others like them getting involved. For instance, showcasing diversity within the climate movement can change people’s perceptions of what a typical “environmentalist” looks like. Highlighting a variety of role models and communicating the norm that many people from diverse backgrounds are actively participating and advocating for climate action may motivate more individuals to get involved.

Methods

The results of this report are based on 2021-2023 data from six waves of the Climate Change in the American Mind survey (n = 6,190) – a biannual nationally representative survey of U.S. public opinion on climate change conducted jointly by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication. Data were collected in March 2021 (n = 1,037), September 2021 (n = 1,006), April 2022 (n = 1,018), December 2022 (n = 1,085), April 2023 (n = 1,011), and October 2023 (n = 1,033). The two survey questions about collective efficacy beliefs were asked in three out of the six waves (December 2022, April 2023, and October 2023) so the sample size is smaller for the analysis of these two questions (n = 3,129). Survey data collection was conducted using the Ipsos KnowledgePanel®, a representative online panel of U.S. adults ages 18 and older. The questionnaires were self-administered online by respondents in a web-based environment.

To measure willingness to engage in climate action, respondents were asked “How likely would you be to do each of the following things if a person you like and respect asked you to?” and provided with a list of actions including: (1) “signing a petition about global warming, either online or in person;” (2) “donating money to an organization working on global warming;” (3) “volunteering your time to an organization working on global warming;” and (4) “writing letters, emailing, or phoning government officials about global warming.” For each of the four actions, those who said they “definitely would” or “probably would” do the behavior in question were respectively categorized as “definitely willing” (four groups) or “probably willing” (four groups). Past engagement in each of the actions is compared across these eight groups.

To measure past engagement in climate action, respondents were asked “Over the past 12 months, how many times have you done the following?” and provided with a list of actions including: (1) “signed a petition about global warming, either online or in person;” (2) “donated money to an organization working on global warming;” (3) “volunteered your time to an organization working on global warming;” and (4) “written letters, emailing, or phoning government officials about global warming.” For each action, those who said they had done it “once” or more often were categorized as “active.” To form subgroups for comparison, respondents who said they “definitely would” do at least one of the four climate actions were categorized as (a) “Definitely willing and active” if they said they had done at least one of the four actions in the past 12 months (“Definitely willing and active”), or (b) “Definitely willing but inactive” if they said they had “never” done any of the four actions. These two groups are compared to all other respondents (“All other Americans”).

Data for each survey wave were weighted to align with demographic parameters in the United States, and then the six survey waves were averaged to take into account sample size differences. Group differences were tested for statistical significance using the weighted proportions and unweighted sample sizes of each group. In figures/data tables, bases specified are unweighted, while percentages are weighted to match national population parameters. The average margin of error is +/- 1.2 percentage points at the 95% confidence interval for the full sample of U.S. adults (n = 6,190). The data tables include the percentages used to develop the charts/figures, the margins of error for each subgroup analyzed, and the wording of the survey questions.