Climate Note · Sep 23, 2021

Americans’ willingness to prepare for “climate change” vs. “extreme weather”

By Jennifer Carman, Karine Lacroix, Matthew Goldberg, Seth Rosenthal, Jennifer Marlon, Abel Gustafson, Peter Howe and Anthony Leiserowitz

Filed under: Behaviors & Actions, Messaging and Policy & Politics

Update July 2022: This publication has been updated with results from the peer-reviewed article, published in the journal Environmental Communication. The updated version is available here.

The impacts of climate change are becoming ever more apparent. The summer of 2021 alone has included record-breaking heat in the Pacific Northwest, flooding in the Midwest, hurricanes in the South, and drought and fires in the West and Southwest United States, in addition to catastrophic fires and floods happening around the world.

As a result, climate change preparedness is growing in importance. However, in the United States, political conservatives sometimes respond negatively to messages that link an event to climate change, even during an emergency. As a result, organizations such as the American Meteorological Society have recommended avoiding the term “climate change” during emergency events and using terms like “extreme weather” instead. Avoiding the term “climate change,” however, may lead people to focus on the symptoms rather than the causes of climate change, thus supporting immediate actions but ignoring and potentially worsening the underlying problem.

This raises the question: Should communicators use the term “climate change” when talking about preparedness, or should they use “extreme weather”? To answer this question, we conducted an experiment measuring Americans’ (N = 1,558) willingness to take preparedness actions and support preparedness policies based on which term was used to describe them. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. The “extreme weather” group (n = 781) was asked about actions to prepare for “extreme weather,” whereas the “climate change” group (n = 777) was asked the same questions, but using the term “climate change.”

We find that the answer to this question depends on who the audience is, as well as the kinds of preparedness behaviors and policies being described.

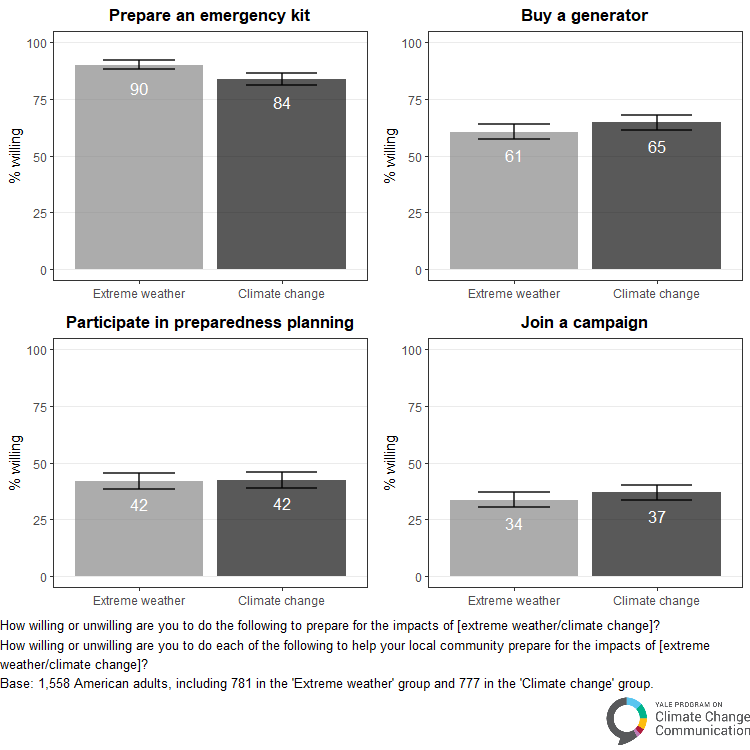

Personal and Collective Preparedness Actions

Most respondents in both conditions said they were willing to take personal preparedness actions such as preparing a home emergency kit (90% in the “extreme weather” (EW) group, 84% in the “climate change” (CC) group), and buying a generator (61% EW, 65% CC). A larger percentage of respondents were willing to prepare an emergency kit in the “extreme weather” group, but willingness to buy a generator did not differ by group.

In contrast to personal actions, less than half of respondents said they were willing to take collective preparedness actions, such as participating in a community effort to develop a local preparedness plan (42% EW, 42% CC) or joining a campaign to convince local leaders to prepare for impacts (34% EW, 37% CC). There were no differences based on the term used.

Preparedness Policies

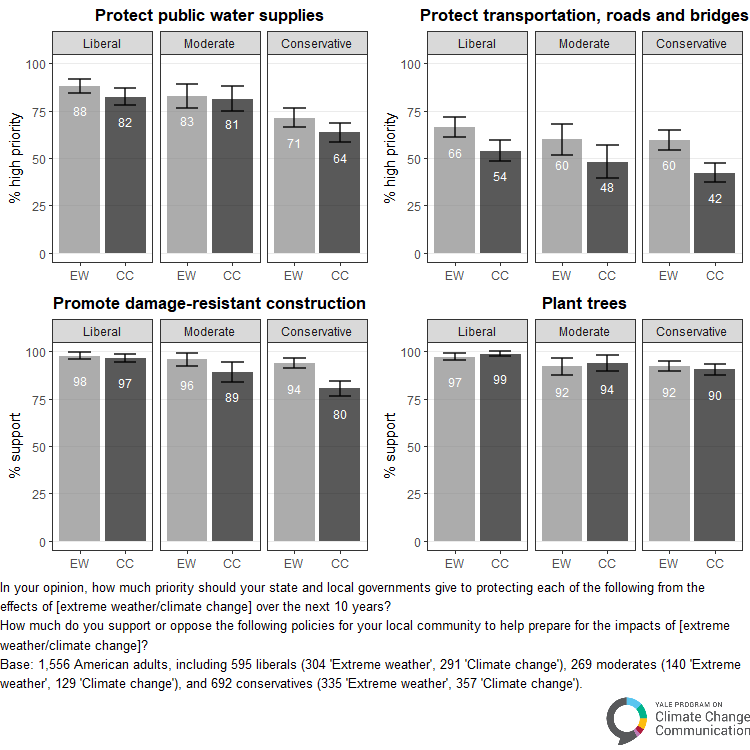

Support for many preparedness policies was high, but using the term “climate change” did have a few negative effects. Regarding policies to protect infrastructure and resources, a larger percentage of respondents in the “extreme weather” group said that protecting public water supplies should be a “high” priority for state and local governments (80% EW, 74% CC). Additionally, support for protecting transportation, roads, and bridges was much lower when the term “climate change” was used than when “extreme weather” was used (62% EW, 48% CC).

In contrast, local policies to prepare for impacts, including promoting construction of buildings that are more resistant to damage from hazards (96% EW, 88% CC) and planting more trees in the local community (94% EW, 94% CC), received high levels of support regardless of the term used.

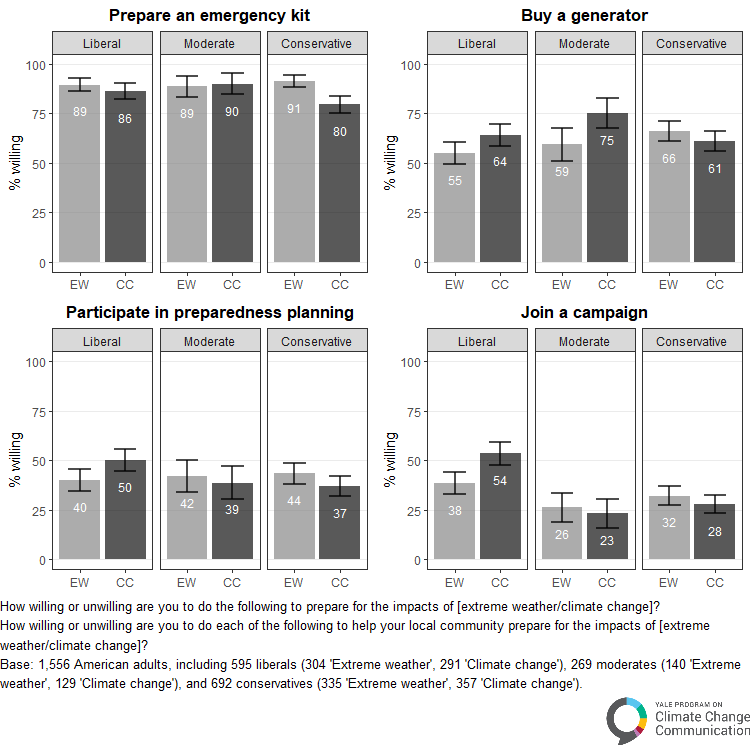

Political Ideology

We also found important differences in reactions to the two terms based on political ideology. Conservatives were somewhat less likely to say they would prepare an emergency kit in response to “climate change” than to “extreme weather,” but their willingness to buy a generator did not differ based on the term. Liberals and moderates did not significantly differ in their willingness to carry out either behavior based on the term.

For collective actions such as participating in preparedness planning, the terms used made little difference for conservatives and moderates. For liberals, however, willingness to engage in these actions — including joining a local political campaign (38% EW, 54% CC) — was substantially higher when these actions were described using the term “climate change” rather than “extreme weather.”

We also found differences in support for preparedness policies based on political ideology. Conservatives were a little less likely to say protecting infrastructure such as public water supplies and transportation should be a high priority when the term “climate change” was used, although a majority still said protecting public water supplies should be a high priority. Liberals’ and moderates’ support for protecting public water supplies did not differ based on the term. Liberals’ support for protecting transportation, roads, and bridges, however, decreased when the term “climate change” was used. Moderates’ support did not change significantly based on the term being used.

For local preparedness policies such as changing construction codes and planting trees, conservative support was lower (although still a substantial majority), when the term “climate change” was used. Liberals’ and moderates’ support for these policies was very high (more than 80%) and did not differ significantly based on the term.

Conclusions

For a politically liberal audience, using the term “climate change” is generally not harmful and can even be beneficial, as in the case of supporting collective actions. Communicators who want to engage liberals will likely find support for many preparedness actions and policies when using the term “climate change.” For an audience of political moderates, using the term “climate change” appears to have little effect, positive or negative, compared with the term “extreme weather,” and is unlikely to be harmful. For personal protective behaviors, infrastructure protections, and planning policies, moderates supported these actions at comparable levels to liberals regardless of the term used. For an audience of conservatives, using the term “climate change” is riskier. Conservatives’ lower willingness to take personal protective actions in the “climate change” group versus the “extreme weather” group is important, because these actions include potentially life-saving behaviors like having an emergency kit. However, conservative support for many preparedness policies remained high, even when they were described in terms of “climate change.” Therefore, when describing some preparedness policies, “climate change” may be acceptable, but in general, using “extreme weather” is likely to be a slightly safer option when engaging with a conservative audience.