In the United States, extreme heat causes more deaths than any other weather-related hazard. Over seven thousand Americans succumbed to the impacts of extreme heat exposure between 1999 and 2009. Physical factors are an important determinant of vulnerability, and small children, elderly people, and individuals with respiratory or heart conditions are at elevated risk during periods of high heat. Psychological factors play an important role in determining vulnerability, too. For example, if an individual doesn’t know the causes or symptoms of heat stroke, or if they are unaware of structural risks in their community’s water, food, or energy supply systems, they are potentially much more vulnerable to the impacts of a heat wave. In other words, knowledge about one’s own vulnerabilities is part of being adequately prepared.

In response to an extreme heat event, Americans are advised to take precautions like drink more water, avoid direct sunlight or strenuous activity, and ensure that pets and young children remain cool and hydrated. People who take heat risk seriously or have been personally affected by an extreme heat event in the past may be more likely to take such precautionary measures or heed government advisories when an extreme heat event is ongoing or imminent.

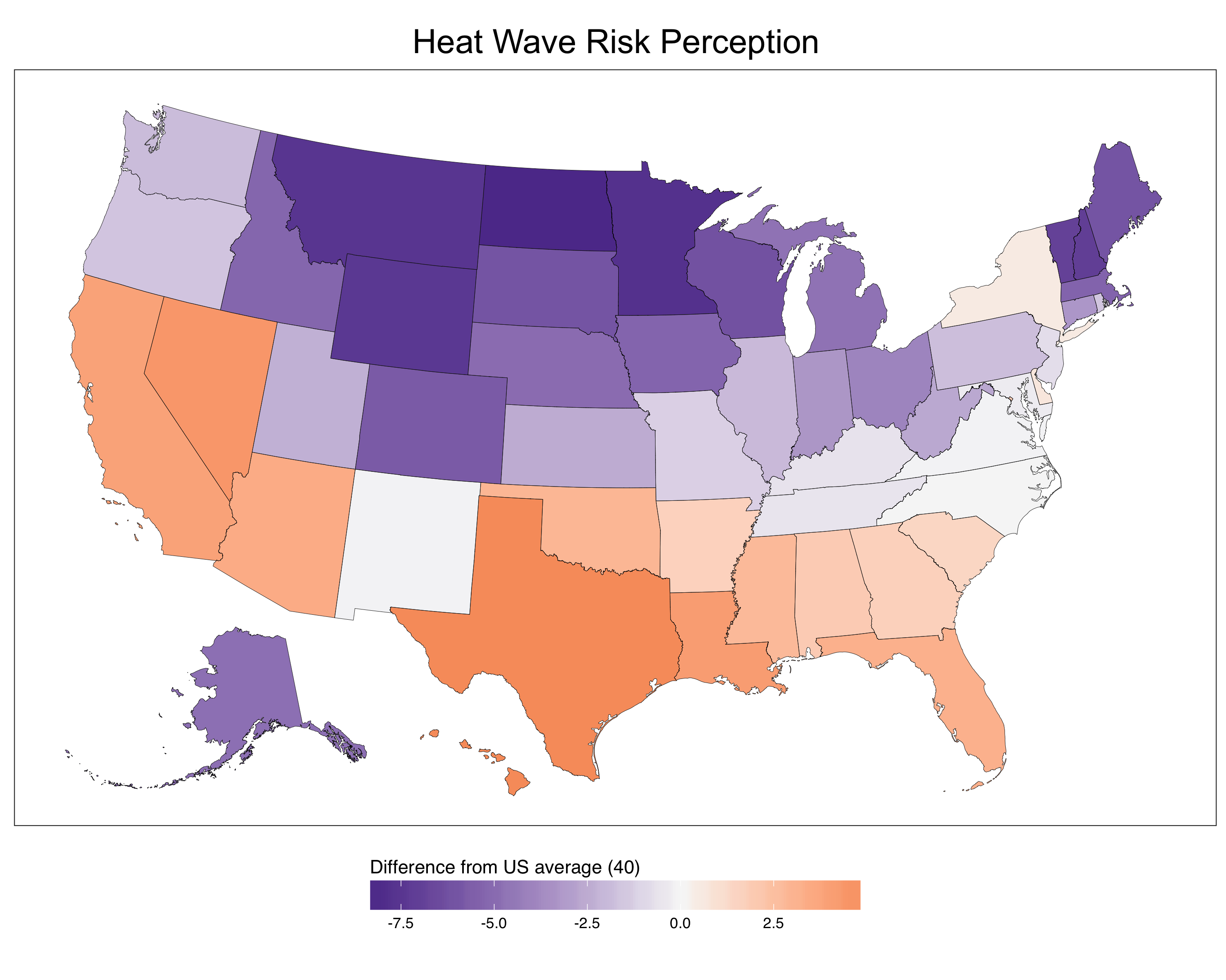

In 2013, a survey conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication found that 85% of Americans had experienced one or more types of extreme weather in the past year, with over half specifically citing extreme heat.[1] Americans accustomed to warm summers with lengthy stretches of high temperatures are likely more familiar with the risks associated with extreme heat events. Preliminary results from national surveys conducted in 2015 by Dr. Peter Howe of Utah State University and the YPCCC show that heat wave risk perceptions in the United States are higher-than-average in southern states and lower-than-average in northern states.[2] Southerners may perceive heat waves as a greater risk than northerners because they have more personal experience with extreme heat events.

Heat wave risk perceptions depart from the national average in a north-to-south pattern. Climate-induced changes in the distribution of heat waves may impact individuals with low perceptions of heat risk (Howe, Marlon, and Leiserowitz, unpublished data).

Heat wave risk perceptions depart from the national average in a north-to-south pattern. Climate-induced changes in the distribution of heat waves may impact individuals with low perceptions of heat risk (Howe, Marlon, and Leiserowitz, unpublished data).

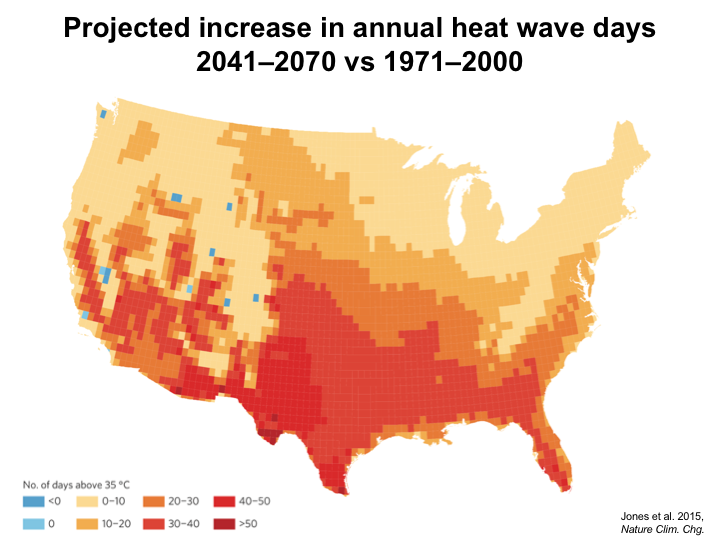

Rising temperatures due to increasing greenhouse gases, however, are creating a mismatch between the distribution of extreme heat events across the United States and the risk perceptions of individuals impacted by those events. In some places where extreme heat days will become much more frequent—states like Wyoming, Utah, Montana, and Colorado in the West, as well as Midwestern states like Minnesota, Nebraska, and North Dakota —perceptions of heat risk are lower than the national average. Model projections show that the incidence, duration, and severity of extreme heat events will continue to increase across the United States as the climate warms.[3] The result is a potential public health crisis that will be aggravated by climate change, as extreme heat events begin affecting people with low perceptions of heat risk and little prior experience of extreme heat. When risk perception does not match threat, individuals and communities may become especially vulnerable to natural hazards.

35ºC = 95ºF. Models project a significant increase in the mean number of hot days experienced in the United States between the late 20th century and late 21st century (Jones et al. 2015).

How should public health officials respond to a likely increase in future heat waves? Communicating the risks of extreme heat should play a central role in policymakers’ responses. To assess perceptions of heat risk around the United States, the YPCCC and its partners undertook a project funded by the National Science Foundation that surveyed Americans’ beliefs and attitudes about extreme heat risk. The project’s results fill a critical knowledge gap by systematically describing heat risk perceptions at national and sub-national scales, with data covering rural and urban areas.

In particular, we find that Americans in northern parts of the country are less worried about heat waves than those in the south, even though northern residents are usually less prepared and are less adapted to heat (e.g., fewer people have air conditioning). In addition, risk perceptions are as variable within a single city as they are between states, highlighting the importance of sociodemographic factors in driving people’s views as well as the importance of targeting risk communication and management to local contexts. New communication strategies will be especially important in regions where perceptions of heat risk may not match the incidence or severity of extreme heat, like in low-income urban areas, and in the Midwest and Rocky Mountain regions more broadly.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation Decision, Risk, and Management Sciences program (SES-1459903). More information on YPCCC’s heat risk research is available here. Several publications are forthcoming based on project results. Join our mailing list to be alerted when they are released.

[1] Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E. W., Roser-Renouf, C., Feinberg, G., & Howe, P. (2013). Extreme Weather and Climate Change in the American Mind, April 2013.

[2] “Modeling geographic variation in risk perceptions as a component of social vulnerability to extreme heat hazards in the U.S.” Presentation by Howe, P.D., Marlon, J.R., Leiserowitz, A., American Association of Geographers Annual Meeting: 23 March 2016.

[3] Jones, B., O’Neill, B. C., McDaniel, L., McGinnis, S., Mearns, L. O., & Tebaldi, C. (2015). Future population exposure to US heat extremes. Nature Climate Change, 5(7), 652.