Blog · June 27, 2020

Connecting the Dots Between Climate Change and Food Systems: How Does Income Relate to Americans’ Food-Related Behavior?

By Urvi Talaty

There are many connections between food systems and global warming. Food systems contribute about 21-37% of total anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. About 10% of total emissions can be attributed to agriculture alone. The systems of production, consumption and food waste have a substantial impact on the environment. Amidst both a warming climate and a growing world population, these systems need to be transformed.

The problem of consumer food waste is particularly acute in high-income countries like the U.S. Studies show that about 30% of food is wasted at the household level in the U.S., which translates to annual consumer‐level food waste worth about $240 billion. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, the higher the household wealth, the more food is wasted. While consumer food waste has traditionally been a problem in higher-income countries, it is also increasingly becoming a concern in emerging economies. Food waste has a substantial impact on climate. Globally, wasted food accounts for 8% of greenhouse gas emissions.

Data from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (YPCCC) and the Earth Day Network’s Climate Change and the American Diet study find that about three in four Americans throw out uneaten or spoiled food “sometimes” (42%), “often” (24%), or “always” (10%) because “they no longer want it or it went bad.” Composting is an effective way to deal with food waste and can help reduce carbon emissions and fertilizer use as well as save money. However, according to our survey data, 72% of Americans either “never” or “rarely” compost food waste.

Here, we examine beliefs and behaviors related to food and climate change across lower-income households (<$50k/year), middle-income households ($50k -$100k/year), and higher-income households in the US (> $100k/year).

Although there are no significant differences in food waste and composting behavior between lower- and higher-income households, higher-income Americans are less likely to perceive a connection between food waste and climate change. Only 40% of higher-income Americans think that if everyone threw away less food, it would reduce global warming by at least “some” as compared to 46% of middle- and 49% of lower-income Americans. Similarly, only 40% of higher-income Americans think that if everyone composted food waste, it would reduce global warming by at least “some” (vs. 47% of middle-income and 49% of lower-income Americans).

Lower-income Americans face more barriers to eating plant-based foods (e.g., fruit, vegetables, plant-based meat/dairy alternatives), which is one of the most effective ways to tackle global warming. For example, lower-income Americans are more likely to say that it is too much of an effort to buy plant-based foods (53% vs. 45% of middle- and 37% of higher-income Americans), and/or that it costs too much to buy plant-based foods (71% vs. 59% of middle- and 46% of higher-income Americans).

When measured by the edible weight or average portion size of the food, fruit, vegetables, and grains are actually less expensive than most meat-based foods (like beef, pork, chicken). However, 53% of lower-income and 52% of middle-income Americans think a meal with a plant-based main course is more expensive than a meal with a meat-based main course (vs. 42% of higher-income Americans).

Environmental and economic reasons to buy plant-based foods are more important to lower-income Americans than higher-income Americans. When choosing to buy plant-based foods, how food companies affect the environment is a more important factor for lower-income Americans than it is for higher-income Americans: 45% of lower-income Americans say that how food companies affect the environment is either “extremely important” or “very important” to them when buying or eating plant-based foods (vs. 38% of middle-income and 37% of higher-income Americans). This may have to do with the growing awareness that low-income populations are disproportionately harmed due to climate change.

Protecting animals is also more important to lower-income Americans. About seven in ten (43%) lower-income Americans say that protecting animals is either “extremely important” or “very important” to them when they choose to buy or eat plant-based food (vs. 36% of middle-income and 25% of higher-income Americans).

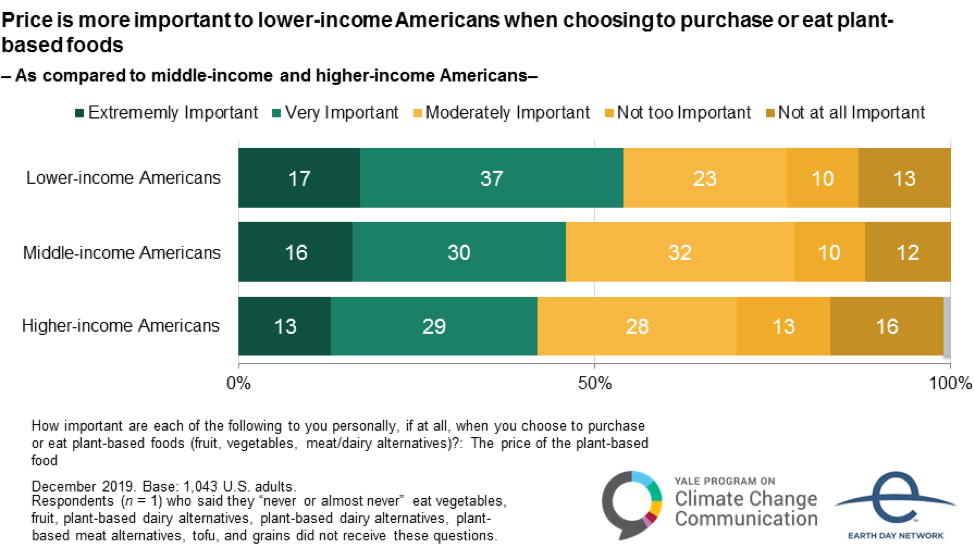

A greater proportion (54%) of lower-income Americans report that the price of plant-based foods is either “extremely important” or “very important” to them when they choose to eat or buy plant-based foods as compared to middle-income (46%) and higher-income Americans (42%).

Lower-income Americans are less likely to buy locally sourced food. More than seven in ten (72%) lower-income Americans purchase locally grown or produced food at least sometimes as compared to 79% of middle- and 81% of higher-income Americans. One potential reason may be the common perception that local food is more expensive, although this is not always true. Eating local food contributes to reducing emissions, even if it is not always as effective as replacing foods like beef in the diet.

There are not significant income differences in Americans who have adopted plant-based diets. People in all three income groups are almost equally likely to be vegan or vegetarian. Overall, however, only 4% of Americans say they are vegan or vegetarian.

The COVID-19 pandemic may influence perceived or actual access to food. Lower-income households experience higher rates of food insecurity and YPCCC surveys have found that access is a larger barrier to the adoption of plant-based diets for lower-income Americans. The current COVID-19 pandemic is making already vulnerable households even more vulnerable to food insecurity. A study by researchers at the University of Vermont found that those with existing food insecurity expressed greater worry about food access during the pandemic and were more likely to use coping strategies such as buying cheaper foods or eating less. Millions more people are newly at risk of experiencing food insecurity, and the COVID-19 pandemic may be exacerbating already existing issues with food access.

These findings provide important insights about how Americans could be engaged in efforts to reduce the impact of food and agriculture on climate change. These data can help identify the most receptive audiences for campaigns to reduce food waste and increase composting, such as low-income communities and help others such as high-income Americans make the connection between food waste and climate change. These results can also help companies better communicate with consumers who are interested in using their food purchases to address climate change. Additionally, the results may help counter certain stereotypes related to socioeconomic status and food choices, and highlight specific food challenges that lower- and middle-income Americans face, as well as prior problems of food insecurity exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, the results can inform policymakers working to reduce the impact of food systems on climate change.

The survey methodology and other details can be found in the Climate Change in the American Diet report.