China has emerged in the 21stcentury as a global superpower, vying for leadership in the Global South with an expansive development plan called The Belt & Road Initiative (BRI). Where the United States under the Trump Administration has withdrawn from international affairs, The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has stepped up to fill the void.

Take the Paris Agreement, for example. A few months ago at COP24, with the United Nations conference tasked with writing a rulebook for the Paris Agreement, US politicians were conspicuously absent. On the other hand, China was praised throughout the conference by foreign ministers, think tanks, and climate activists alike as a torch bearer, a global driver of clean energy. The BRI in particular, representing $1 trillion of Chinese investment across 65 countries, was described at COP24 as spreading “ecological civilization” around the globe, a term coined by the leading Chinese political party to represent simultaneous economic development and environmental protection.

Indeed, it is hard to imagine anything sounding more ideal than global ecological civilization. Xie Zhenhua, the lead UN climate change negotiator for China since the Paris Accords, claims that the BRI is a new form of international “climate change governance” that will create a “community of common destiny.” And at the COP24 China Pavilion in December, a strong emphasis was placed on China’s development aid as South-South cooperation.

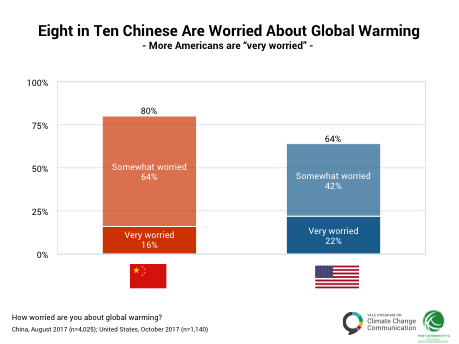

But but so far, the BRI could be doing more to deliver on its promise to spread green infrastructure and sustainable development. In nations where projects are already under construction, common destiny is often sidelined while China builds marine ports, railroads, and power plants that are more polluting than would be allowed domestically. At COP23 in Bonn, Germany, results from a 2017 survey by the China Center for Climate Change Communication and YPCCC showed that the Chinese public strongly supports climate action both domestically and internationally. Is the Belt & Road Initiative spreading sustainable development from one Global South nation to sixty-five others, or is China raising only its domestic standards while exporting emissions abroad? With its name alone, a parallel is being drawn between the reach of China during the Silk Road era and the new Belt & Road Initiative.

Today, China is building dams in Sudan and railways in Nigeria. As sub-Saharan African nations take out massive loans to finance these major infrastructure projects that also result in uncalculated environmental losses, many face a looming debt crisis, with money largely owed to China. In Southeast Asia, Laos took out an $800 million loan from a Chinese bank to help build a railroad, and the IMF said public debt could rise to as much as 70% of the economy. In Malaysia, one of the countries receiving the most Belt & Road investment, the current Prime Minister Mahathir Bin Mohamad ousted his opponent on the platform that the nation was “selling the country’s sovereignty” by allowing China access to strategic ports and trade corridors.

China is funding mega-infrastructure projects throughout the developing world, often promising sustainable infrastructure and falling short. Consequences range from environmental degradation, to the spread of soft power, to debt crisis or undermined sovereignty.

Aggressive low-carbon policies, including record-breaking investments in renewable energy and the introduction of the world’s largest Emissions Trading System, rightfully earned China praise as a torch bearer at COP 24 in Katowice. With eight in ten Chinese worried about global warming and supportive of global climate leadership, Beijing has a strong incentive to rise up and take the lead on international climate action. Such a commitment to a worldwide low-carbon future requires not only domestic improvements, but also a serious commitment to greening Belt & Road infrastructure.

According to Helen Mountford, World Resources Institute VP for Climate & Economics, the feasibility of China’s green common destiny laid out at COP24 depends entirely on the design of Belt & Road infrastructure in next two to three years. If the projects planned now, which will be implemented in the next decade or two, are sustainable and low-impact, the BRI could end up paving much of the Global South with necessary green infrastructure for the future. However, China’s leveraging of sustainability and South-South cooperation rhetoric is– for now– mostly talk.

Additional Links:

Moving the Green Belt and Road Initiative: From Words to Actions – World Resources Institute Report

Behind China’s $1 Trillion Plan to Shake Up the Economic Order – New York Times

Malaysian PM Mohamad moves to cancel $22 billion of Chinese-funded BRI projects – Video

Sources:

Heidi Wang-Kaeding, “What does Xi Jinping’s New Phrase ‘Ecological Civilization’ Mean?” The Diplomat, March 06, 2018.

Xie Zhenhua (speech, COP24-Katowice, Poland, December 12, 2018).

Jane Perlez & Yufan Huang, “Behind China’s $1 Trillion Plant to Shake Up the Economic Order,” New York Times, May 13, 2017.

Stephan F. Miescher, ‘‘Nkrumah’s Baby’’: the Akosombo Dam and the dream of development in Ghana, 1952–1966,” Water History6, (2014): 341–366.

“Zambia’s looming debt crisis is a warning for the rest of Africa,” The Economist, September 15, 2018.

Liz Lee, “Selling the country to China? Debate spills into Malaysia’s election,” Reuters, April 26, 2018.

Secretary of Environmental and Natural Resources Roy Cimatu, Philippines (speech, COP24-Katowice, Poland, December 13, 2018).

James A. Millward, “Opinion: Is China a Colonial Power?” New York Times, May 4, 2018.

World Resources Institute Vice President for Climate & Economics Helen Mountford (speech, COP24-Katowice, Poland, December 13, 2018).