Blog · February 11, 2017

Trump, Climate Mobilization, and the Alarmed

This blog post was written by Nathan Lobel, Yale College ’17.

As those familiar with the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication know, our research goes beyond whether people believe that the climate is changing. We dig deeper, aiming to uncover the ways that people think about climate change in all its many facets. Do they believe that climate change is caused by human activity? Who do they think will be most affected by these changes? And what should be done to prevent climate change’s most dangerous effects?

Communication know, our research goes beyond whether people believe that the climate is changing. We dig deeper, aiming to uncover the ways that people think about climate change in all its many facets. Do they believe that climate change is caused by human activity? Who do they think will be most affected by these changes? And what should be done to prevent climate change’s most dangerous effects?

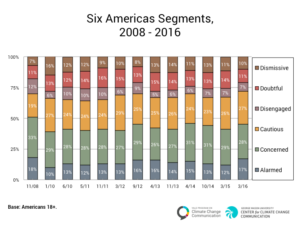

In our “Six Americas” framework, we try to group people’s opinions on climate change. They might be Dismissive, Doubtful, Disengaged, Cautious, Concerned, or Alarmed.[1] The Alarmed are the most likely to take political action on climate to advocate for emissions reductions. In contrast, the Dismissive strenuously fight against energy regulation. In the past, those dismissive about climate change (9 percent of the population by our most recent survey) have had an outsized influence in our political process. After a primary season when only one of seventeen Republican presidential candidates acknowledged the reality of climate change, many might be surprised to learn that nearly half (49 percent) of all Trump voters believe that global warming is happening, and 62 percent support taxing or regulating global warming pollution.[2]

Membership in the Six Americas is fluid though, and there may be reason to believe that more Americans will become engaged in the fight for climate action in the coming years. In a recent article for The New Yorker, columnist Jelani Cobb argued that Trump’s presidency could catalyze the birth of a new generation of activism.[3] According to Cobb, “movements are born in the moments when abstract principles become concrete concerns.” Therefore, Cobb implies that movements arise in response to moments of crisis: Occupy Wall Street was a reaction to the financial crisis, and Black Lives Matter was inspired by the shootings of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. Cobb seems to believe that moments of crisis, when principles are tested in concrete ways, will be plentiful over the next four to eight years. So far, his prediction seems sound: Masses have already taken to the streets to express disapproval for President Trump’s treatment of women[4] and temporary ban on immigration from seven predominantly Muslim countries.[5]

Membership in the Six Americas is fluid though, and there may be reason to believe that more Americans will become engaged in the fight for climate action in the coming years. In a recent article for The New Yorker, columnist Jelani Cobb argued that Trump’s presidency could catalyze the birth of a new generation of activism.[3] According to Cobb, “movements are born in the moments when abstract principles become concrete concerns.” Therefore, Cobb implies that movements arise in response to moments of crisis: Occupy Wall Street was a reaction to the financial crisis, and Black Lives Matter was inspired by the shootings of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. Cobb seems to believe that moments of crisis, when principles are tested in concrete ways, will be plentiful over the next four to eight years. So far, his prediction seems sound: Masses have already taken to the streets to express disapproval for President Trump’s treatment of women[4] and temporary ban on immigration from seven predominantly Muslim countries.[5]

However, social movement theorists argue that people do not protest simply in response to bad conditions, but rather when conditions are improving but those improvements appear on the verge of being snatched away.[6] People do not mobilize until rising expectations are crushed. It could be argued then that the Black Lives Matter Movement did not form only as an eruption of discontent about state-sanctioned violence, but also as the promise of a post-racial America after the election of Barack Obama was shown to be hollow. Though this understanding of movements nuances Cobb’s, it also supports his thesis. Obama shaped his presidency in part around his campaign promise of hope. Now, many of his policies – including environmental protections – may be imperiled.

The election of Donald Trump suggests that this trajectory could soon describe American climate politics. Many states began to take action on climate during the Bush years. With the election of Barack Obama, climate change mitigation became federal policy. The president capped emissions from power plants, raised fuel efficiency standard for cars, and helped to negotiate an international treaty to address climate change. Donald Trump now pledges to ditch emissions caps and pull the U.S. from the Paris Climate Accord. These actions could easily dash Americans’ rising expectations for climate action.

People hoping to mobilize will likely find fertile soil in which to build a movement. Another lesson from social movement theory is that movements do not emerge spontaneously but rather build upon the scaffolding of existing social connections and networks to recruit and mobilize participants.[7] This too strengthens Cobb’s prediction that movements are likely to form: there has been no shortage of organizing on climate change over the past few years. In 2014, 400,000 people marched in the People’s Climate March in New York City to demand climate action. Since 2012, over 1,000 local organizations have sprung up to fight for their cities, churches, and colleges to divest their endowments from the fossil fuel industry.[8] And resistance to fossil fuel infrastructure, like the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline in North Dakota and the Keystone Access Pipeline, has sparked solidarity protests across the country. The networks forged by these protests will likely prove useful to organizers trying to build a greater climate movement.

What does all of this mean for YPCCC’s research? One marker of the Alarmed category is its members’ willingness or desire to participate in a campaign to convince elected officials to address global warming. If a movement develops, it will likely do so by converting some of the Concerned, Cautious, Disengaged, or even Doubtful into Alarmed. The proportion of Americans alarmed by climate change has already grown to match the highest level since we began conducting surveys in 2008. If President Trump chooses to roll back progress on climate change, this percentage could well climb even higher.

[1] http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/six-americas-2016-election/

[2] http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/trump-voters-global-warming/

[3] http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/01/09/the-return-of-civil-disobedience?mbid=social_facebook

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/01/21/world/womens-march-pictures.html?_r=0

[5] http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/01/29/512250469/photos-thousands-protest-at-airports-nationwide-against-trumps-immigration-order

[6]Denton E. Morrison. 1971. “Some Notes Toward Theory on Relative Deprivation, Social Movements, and Social Change.” American Behavioral Scientist, 14: 5. pp. 675-690 .

[7] Jo Freeman. 1973. “Origins of the Women’s Liberation Movement.” American Journal of Sociology. 78:4. pp. 792-811.

[8] Go Fossil Free. Accessed 12/26/16 https://campaigns.gofossilfree.org/