Blog · October 27, 2016

Trust Issues in the Climate Change Debate (And How Culture Can Help)

Why aren’t the bare scientific facts enough?

It can be hard to truly persuade people that human-caused climate change is a threat to society. People aren’t particularly moved when presented with the scientific facts about climate change, but why is this the case? Part of the problem is communicating the facts themselves. Climate science is complex, and so much of climate communication work involves finding clear, effective ways of explaining what scientists are saying. [1] [2]

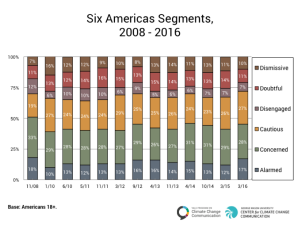

Scientific consensus is strong: 99% of climate scientists agree that human-caused climate change is a threat. With this strong support, it may seem that communicating facts about climate change is straightforward, and that climate denial arguments would fail to persuade anyone at all.[3] But only 10% of Americans knows about the scientific consensus, and of the 90% who do not, there are a puzzlingly wide range of attitudes about climate change. 55% of American adults are either cautious or concerned about global warming, and 22% are either doubtful or dismissive. And 17% are alarmed – a higher percentage than Americans who know about the scientific consensus on climate change.[4][3] These opinions must be coming from somewhere. But if most American adults aren’t aware of the scientific consensus, then what shapes their views?

Trusting climate science means trusting climate scientists

In their book “Climate Change as Social Drama,[5]” sociologist Philip Smith and environmental scholar Nicolas C. Howe argue that culture is at work. “Culture” is made up of systems of symbols that humans use to organize and make sense of their experiences in the world. Depending on their membership in different groups – nations, ethnicities, genders, social classes, etc. – people learn to use these cultural codes until their particular way of understanding the world becomes as habitual as breathing.

Howe and Smith argue that cultural codes strongly influence which claims about climate change people will find most persuasive, from what they accept as scientific fact, to whether they are willing to go against scientific consensus even when aware of it.

People without the scientific knowledge to evaluate the latest IPCC report themselves will decide instead whether or not to trust the authors of the report. More specifically, they have to decide whether they trust those scientists more than they trust opponents of climate change. Members of an audience never evaluate the legitimacy of climate science based on facts alone; they always also evaluate the person delivering those facts.

So how do people evaluate the legitimacy of speakers? Howe and Smith say it depends on whether an audience believes that the speaker exhibits three key qualities: technical competence, moral character, and good will towards the audience. Most people cannot evaluate the technical competence of scientists and their opponents, so they make do with trying to guess who is virtuous and has their best interests at heart.

A large part of cultural systems consists of concepts defined by opposition to another concept: hot vs. cold, reasonable vs. unreasonable, good vs. evil. These are organized into cultural codes (or discourses) that tell us which concepts we should expect to see together. For example, good people tend to be reasonable instead of unreasonable. Cultural codes tell us not only what “good” and “evil” are, but also what signs to look out for when trying to categorize someone.

This is the unseen factor influencing whether people are worried about global warming: the extent to which public speakers are able to model the “good” side of an audience’s cultural-specific codes and appear credible.

Climategate: climate scientists on the wrong side of a cultural code

One of the most important cultural codes in the United States, according to Howe and Smith, is the “discourse of democratic civil society.” Public figures must do everything they can to be seen as “civil” by their audiences, and to frame their opponents as “uncivil.” If a person displays openness, control, and reason, they are perceived as trustworthy; secrecy, pettiness, and emotion will connote an “uncivil” and untrustworthy figure.

If anything shows how easily public trust in scientists can deteriorate, it’s the “Climategate” incident. Howe and Smith point to Climategate as an example of cultural codes leading people to doubt climate change and climate scientists. On November 2009, the Climate Research Unit (CRU) at the University of East Anglia was hacked, and emails, documents and source code were leaked. Climate skeptics presented email excerpts, claiming evidence of scientific fraud. One email spoke of a “trick” to “hide” a decline in global temperatures. Howe and Smith observe that other emails mentioned “boycotting a refereed journal which published climate skeptical knowledge, deleting certain emails before a Freedom of Information Act request made them available, and being tempted to ‘beat the crap’ out of climate change skeptic Pat Michaels.”[5]

Pope Francis’s call to action: the right side of a cultural code

Culture codes aren’t just pitfalls to avoid in crafting climate change messages. Speakers on the right side of a cultural code can have powerful, positive effects on climate action.

In June 2015, Pope Francis issued the encyclical Laudato Si’: On Care for our Common Home, which urges Catholics to enter a conversation with one another, and with all of humanity, about

the implications of climate change and environmental destruction. He argued that climate change threatens the world’s poorest and most vulnerable, and that the moral course is to take action.

The Pope’s message had an appreciable impact: about 8% of American adults and 17% of American Catholics said that his message made them more concerned about global warming.[9] It’s worth remembering that the effectiveness of the Pope’s message wasn’t just its contents, but also because the Pope was the one delivering it. To many Catholics, Pope Francis is without a doubt on the right side of the cultural-moral code. He is by no means a qualified authority on climate science, but he carries a powerful credibility of his own because of his status as a religious leader.

Becoming someone credible

As climate change communicators, we must aspire to be on the right side of our audiences’ cultural codes. We should pay more attention to how our audiences see us as people, not just how they see our issue. This won’t happen if we approach skeptics with contempt.

Whatever facts we present can only be persuasive if our audience believes we are credible and trustworthy messengers. Speaking the truth isn’t enough – good people must be speaking it.

[1]“Simple Messages Increase Understanding of the Climate Change Consensus” (YPCCC)

[2] “How to Communicate the Scientific Consensus on Climate Change” (YPCCC)

[3] “Climate Change in the American Mind: March, 2016” (YPCCC)“Climate Change in the American Mind: March, 2016” (YPCCC)

[4] “Scientific Consensus on Climate Change as a Gateway Belief” (YPCCC)

[5] Climate Change as Social Drama

Global Warming in the Public Sphere (Philip Smith, Nicolas Howe)

[6] “‘Climategate’ review clears scientists of dishonesty over data” (The Guardian)

[7] “The Independent Climate Change E-mails Review” (University of East Anglia)

[9] “The Francis Effect: How Pope Francis Changed the Conversation About Global Warming” (YPCCC)